Verhoeven Vision

December 17, 2025

Jay RameyLiving in a Paul Verhoeven timeline is bad enough, but is there a Verhoeven aesthetic that's separate from '80s retro-futurism?

After being trapped in a Paul Verhoeven movie for the past decade, we are now quickly approaching the Alfonso Cuaron future depicted in Children of Men (2006), many elements of which had already materialized during the pandemic. Some have argued that much of the Cuaron future is already here, as a result of wars, waves of migration from areas of societal collapse, ubiquitous surveillance, and the high-tech militarization of police.

If there is any consolation, we are still some years away from a more unnerving Neill Blomkamp future, seen in the short film in the Tetra Vaal (2004) and Elysium (2013). Though we have been getting previews of that universe as well.

These three futures appear to overlap in certain news cycles, but the dominant vibe still feels mostly Verhoevean, thanks entirely to the current political and business landscape being peopled by on-the-nose Paul Verhoeven characters, as David Roth noted five years ago in a very observant New Yorker article. Perhaps the most relevant of Verhoeven’s films is still the 1987 classic RoboCop.

The social commentary of the film, especially as viewed in much later years, almost upstaged the plot and the main character himself. The film depicted a corporatist future with fascist overtones, a consumer society taken to an uncomfortable extreme, the militarization of police, and an urban dystopia with decaying infrastructure.

The short-lived 1994 RoboCop: The Series expanded on these themes further, adding particularly prescient cyberpunk visuals with Toronto standing in for a future Detroit. Among other things, it previewed the opioid epidemic, rampant cybercrime, and the Flint water crisis, of all things. It was also far heavier on the use of military vehicles by police forces, and other things we now see as commonplace if not exactly “normal,” because we’ve become somewhat desensitized to them over the years.

But the 1987 film also created a certain aesthetic, one that is dominated by gray and metallic colors, austere shapes, brutalist architecture, cold neon lighting, and graffiti-covered concrete surfaces. To be sure, many of the things that are examples of ’80s retrofuturism inevitably have a Verhoevean feel to them, so there is a lot of overlap.

But the crucial Verhoeven aesthetic test is: Could you picture this product being in the background of a Verhoeven film?

If there is one recent product category that absolutely dominates current examples of the Verhoeven aesthetic, it is (surprise!) robots of all shapes and sizes.

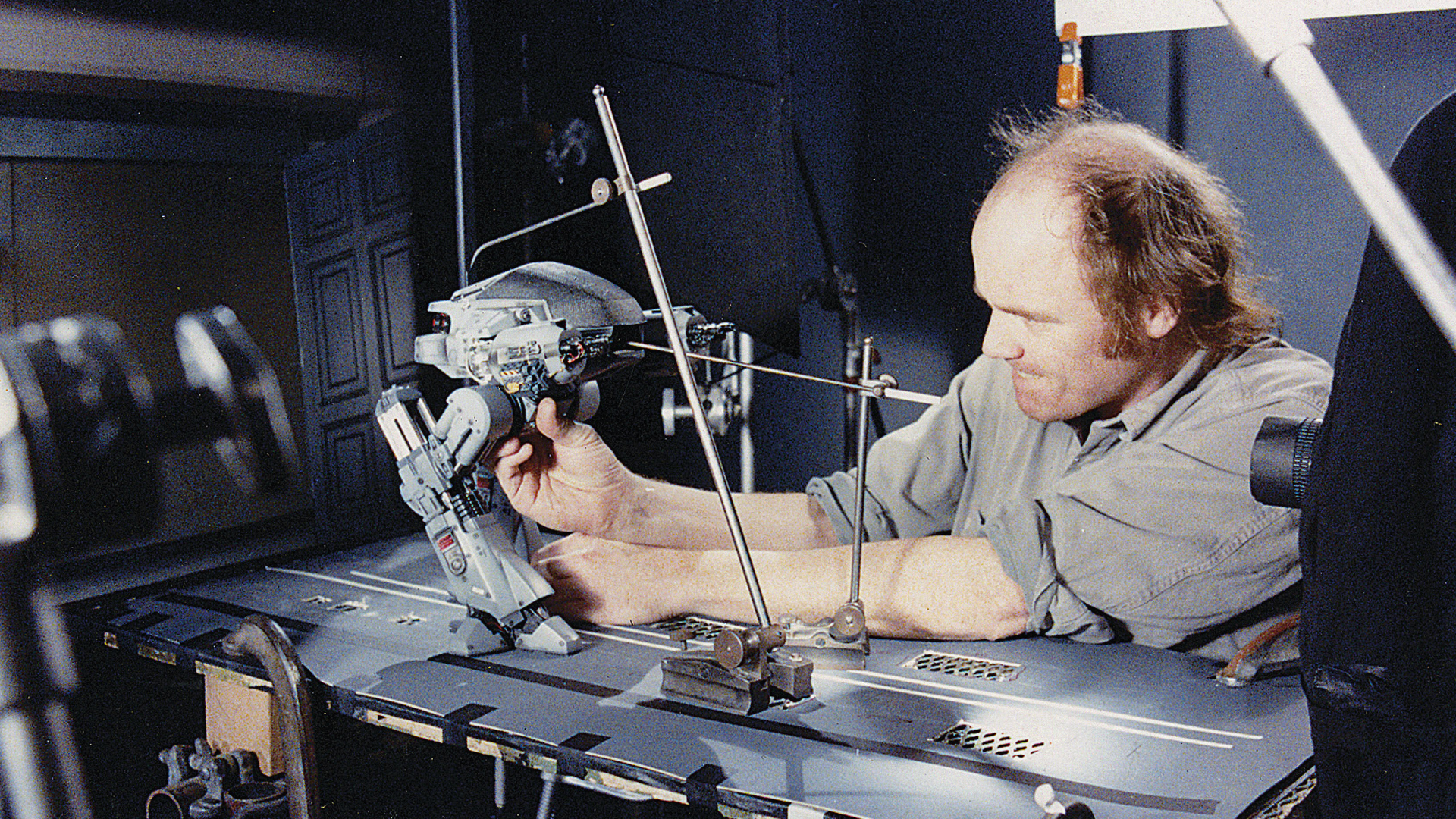

The ED-209 robot in the RoboCop films — deliberately designed to look car-like — displayed a lot of the core elements of the Verhoeven aesthetic. These days it’s an even more relevant reference point than cars due to the proliferation Verhoevian robots. Its chunky legs and arms, gray colors, and a rectangular design feature at the front, just like on the 6000 SUX luxury car, defined the look of the robot.

One recent robot that might pass the Verhoeven film background product test is the Diablo Wheeled Bipedal robot, pictured below, which has an ability to balance on its two wheels.

Already featuring an industrial look, the robot’s front yellow visor mirrors the look of quite a few robots in Verhoeven’s RoboCop, though certainly not all of them. But it still seems like a product that could be seen in the background of a Verhoeven film.

Thankfully, the Diablo robot is far smaller in real life than it would have been in RoboCop.

Another recent wheeled robot likely passes the “could you picture this product in the background” test. And it’s Nuro’s R2 delivery robot, first seen in 2020.

Finished in cheerful colors, the Nuro R2 may not seem like a prime example of this design aesthetic, at least at first.

But, strangely enough, if viewed in a black and white photo the R2 delivery robot begins to look a bit different, and arguably like something that could have been in one of the RoboCop films.

We’re also seeing more tracked robots designed for work in war zones. The conflict in Ukraine has already experienced the deployment of several such machines.

One is Milrem Robotics’ THeMIS, which can serve as a combat robot with a mounted machine gun, and also as a cargo carrier that can evacuate wounded from the battlefield. It arguably passes the Verhoeven test as well, and comes close to replicating ED-209’s capabilities.

“The THeMIS is a versatile, powerful and cost-effective combat asset. It supports troop movement and adapts rapidly to changing battlefield conditions and needs,” the company says.

Milrem Robotics notes that it’s already been deployed in Ukraine and Mali, and has been purchased by 19 different countries.

It’s not autonomous or powered by AI, at least not yet, so we still have some time before we’ll need to present our papers to a similar robot parked in front of an office building.

When it comes to vehicle design, the 6000 SUX may have been one of the star cars of the film, but it was just one small representation of the Verhoeven aesthetic in automotive design. The car’s moon disc wheelcovers — a retro-futurist styling staple by now — were one of its more memorable elements, which is perhaps why the Tesla Cybercab instantly triggered that association for some observers.

If there is one particularly commonplace product that I’ve been avoiding mentioning so far, because it’s so obvious, it’s certainly an electric truck.

But is the Cybertruck reflective of the Verhoeven aesthetic?

It certainly feels like it wants to be. And it embraces the fact that it’s dystopian.

I would argue that the Cybertruck is an outlier in how in how retro-futurist it is. It was designed with wedge-like shapes of the 1980s in mind, down to the graffiti-style logo. And it almost feels like it’s too much of a caricature to seem believable if it appeared in one of Verhoeven’s films.

Still, the Cybertruck feels very much a part of the Verhoeven Cinematic Universe, so it passes the test. And it’s far from the only example of this design direction seen in recent years, with the aesthetic not even remaining confined to cars or robots.

Tesla’s Optimus robot, meanwhile, has steered clear of Verhoeven’s metallic gray colors, but the overall design of this robot (and its various mishaps) inevitably have a Verhoeven feel to them.

A recent video making the rounds, in which the Optimus robot’s operator appears to try to take off his headset with the robot promptly falling over, reminded me of the failed RoboCop prototype scene in the second film where one of the prototypes tries to take off his helmet and falls over.

Some urban transportation concepts and production models have drifted toward a Verhoeven aesthetic in recent years, often without realizing it.

The 2014 R1 tram concept by UralVagonZavod in Russia sent chills down the spines of plenty of design students and urban architects, creating a sharp contrast to the beloved red Tatra trams of decades past, once common all over Eastern Europe.

As one might expect, the design has been criticized as particularly dystopian, though perhaps largely due to its dark colors. If finished in a different color scheme like white and jelly red or orange, I suspect, it could see far more friendly. Incidentally, this is why color is important to the Verhoeven aesthetic.

Yet another robot, this time by Hyundai Motor Group, has seemingly nailed all the Verhoeven elements including the moon disc wheels and the gray color, if not the sheer scale of most of the robots in Verhoeven films.

Aimed at use cases as varied as film production and logistics, the MobED concept robot features “AI-based” autonomous navigation and lidar sensors.

“MobED’s design embodies the ‘Refined Edge’, a harmony of straight lines and flowing curves that balances technical precision with understated elegance,” Hyundai says.

More importantly, if this robot was the size of a pickup truck and not a shopping cart, it would be extremely easy to picture in the background of a Verhoeven film.

But ultimately, it’s not the designs that look like they could appear in a Verhoeven films that should be feared or derided. Rather, it is everything else that was seen in his films, including ultra-powerful corporations running cities, militarized police forces, a violent political culture, a greed-based corporate culture reinforced by technology, and commonplace gun violence in a population desensitized to gore.

The aesthetics are only noticeable because it feels like we are living in one of Paul Verhoeven’s films at the moment, while moving into Children of Men and waiting for a messier and perhaps more sinister Neill Blomkamp future to arrive.

Recent Posts

All PostsMarch 2, 2026

February 27, 2026

February 26, 2026

Leave a Reply