Pancake Power

December 29, 2025

Lawrence Ulrich

1000 horsepower from a motor that fits in a backpack. Is this what EVs have been missing?

In any rational world, or any previous era, the gasoline engines in the Ferrari 296 Speciale and Lamborghini Temerario would be standalone superstars.

Transparently encased in these midengine supercars, like Louvre jewels ripe for plucking, the Ferrari’s V6 coaxes 690 horsepower from 3.0 liters of displacement. The Lamborghini’s 4.0-liter V-8 counters with not just 789 horsepower, but a madcap 10,000 rpm redline. Ho hum, it’s merely the world’s highest-revving series-production V-8.

Yet as the ball drops for 2026, into a billionaire’s bacchanal littered with more supercars and hypercars than ever, even these works of internal-combustion art are no longer enough; as I learned during whipcracking drives of both hybrid supercars at their respective homes in Emilia-Romagna. Despite their unbelievable powerplants, both need additional electric feeding to keep pace with the times. After all, a Corvette ZR1X, as unmentionable here in Italy as an executive’s side dish, brings 1,250 hybrid horsepower and a 233-mph top speed, for $207,000. If you had said even 10 years ago that your neighborhood Chevy dealer would sell a 1,250 horsepower hybrid Corvette, your bartender would have cut you off.

The point is that, when enthusiasts complain (and complain) that electrified cars are the death of driving fun, I want to smack them — or enlist them in the revolution that’s apparently unfolding beneath their petrol-sniffing noses. Sure, full EVs are hitting a lull in the U.S., too expensive or inconvenient for many buyers. But as the world’s leading go-fast brands have learned — Ferrari, Lambo, McLaren, Porsche, Koenigsegg, Mercedes-AMG, Corvette — internal combustion alone can no longer compete straight-up with electrified powerplants. They will no longer match the power, instant torque, acceleration or traction advantage of electric motors, which can sense and react to wheelspin roughly 100 times faster than ICE powertrains. On the Formula 1 grid for 2026, half the power will come from hybrid electricity. Before 2027 is out, fully electric sports cars will finally enter the fray, fulfilling the promise of the primitive Tesla Roadster way back in 2008. (Market unicorns like $2.5-million Rimacs don’t exactly count).

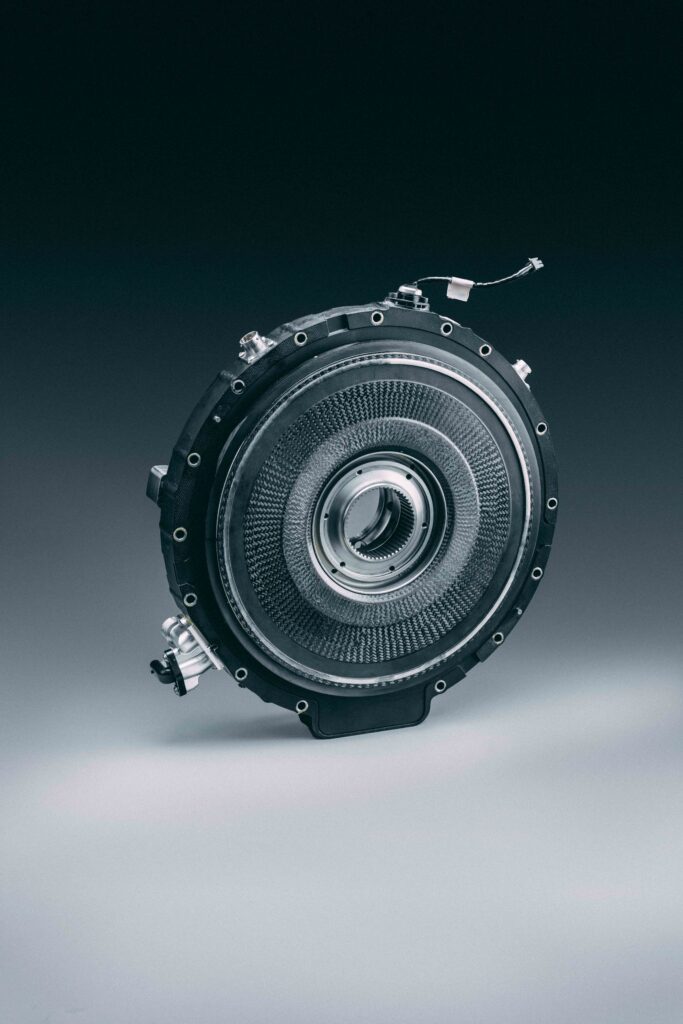

Yass, it’s YASA

The crazy part? A single company is at the forefront of this revolution, in both hybrids and EVs: YASA. The U.K company pioneered series production of axial-flux motors, solving a riddle that had flummoxed engineers for more than a century. Founded by Tim Woolmer in 2009, a spin-off of his Oxford engineering PhD, YASA applied his breakthroughs in the star-crossed Jaguar C-X75 concept in 2010. The $1.9 million Koenigsegg Regera marked a production-car debut, three motors supplying nearly 700 of the Regera’s 1,500-plus horsepower, no transmission required. Next came the Ferrari SF90 Stradale, the brand’s first hybrid, followed by the Lamborghini Revuelto and McLaren Artura. The world’s fastest electric plane, the Rolls-Royce Spirit of Innovation, integrated three YASA motors to achieve a 345.4-mph top speed.

Which brings us to the 296 Speciale and Temerario hybrids: Both great, grazie, the Ferrari is a bit better, its wizardly tech integrated in a more holistic, transparent fashion. But on roads that curled like strands of the local tagliatelle, both cars’ combo of peak-tech ICE with axial-flux boost shows where this is all heading, quickly.

The Ferrari’s single YASA motor sends 178 horsepower to rear wheels exclusively, bumping the 296 Speciale to a “competitive” 868 horsepower. On the company’s Fiorano circuit, the track-focused Speciale sets an indescribable, interstellar pace. I’ve driven probably 10 Ferraris on this track, and I can’t name one – including the SF90 – that feels quicker, as responsive or thrilling to drive. Ferrari’s own test numbers prove as much, including objective measures of what makes a sports car “fun.” By design, this Ferrari hybrid becomes the most engaging, driver-centric car in its lineup.

The Lamborghini integrates three YASA motors. A pair on the front axle supply AWD traction and a peak 294 horsepower, more by themselves than an average passenger car. A total of 907 hybrid horsepower sends the Temerario to a 213-mph top speed. The motors ably fill any gaps in gasoline acceleration, including sustaining thrust during upshifts. Electric torque-vectoring lets the Temerario catapult out of corners with ridiculous force and control, yet this supercar feels surprisingly natural and tossable.

The Axial Advantage: What Took So Long?

Tesla was the first to patent an axial-flux design — Nikola Tesla, that is, back in 1889. It would be 126 years before the concept found its way to automobiles like the Koenigsegg. Today, the world’s EVs and hybrids rely almost entirely on radial-flux motors, which have dominated for well over a century.

Simon Odling, YASA’s Chief of New Technology, explains how the company cracked the code. Picture an electric motor, with its barrel or sausage shape. That’s a radial flux unit, with flux being the number of magnetic field lines that move through a given surface. Flux moves radially, meaning perpendicular to the motor’s central shaft. Like a sausage casing, a stator’s fixed frame surrounds a rotor. Stator magnets generate a field that spins a rotor to generate torque. But that rotor, surrounded by a stator, is relatively small. With torque proportional to the square of the rotor diameter, that means less torque in a given space.

An axial flux design is more like a pancake, with cooling oil as the syrup. A circular rotor sits alongside the stator and nearly matches its diameter, dramatically expanding the magnetic surface area. Flux moves axially, or parallel to the shaft. And YASA’s dual-rotor design puts a rotor on either side of the stator, effectively doubling the torque-generating elements, and shortening the magnetic path.

The result? Odling says the company’s motors take up half the volumetric space and weight of a radial machine, yet are decisively more powerful. Today’s supercars demonstrate the upsides for vehicle packaging and weight savings.

“The motor sits between an engine and gearbox really nicely in a hybrid application, or makes for a very compact drive unit in an EV,” Odling says. “We see the route to building very lightweight, exciting, high-performance sports cars.”

The company’s latest prototype might open anyone’s eyes.

It generates 1,005 peak horsepower and up to 536 continuous horsepower. This compact powderkeg weighs 27.9 pounds. A 1,005-hp power source, that you could carry in a backpack. It’s insane, but real.

“This isn’t a concept on a screen — it’s running, right now, on the dynos,” Woolmer says. “We’ve built an electric motor that’s significantly more power-dense than anything before it, all with scalable materials and processes.”

A density of 59 kilowatts per kilogram is an unofficial world record. That’s nearly three times as power-dense as leading radial designs, including Tesla’s.

The company’s name offers another clue to its technical edge: YASA stands for “Yokeless and Segmented Architecture.”

The units eliminate a weighty iron or steel yoke, the traditional backbone for conductive copper coils. Where a conventional motor might have 65 pounds of iron, a comparable YASA design requires roughly 12 pounds. Woolmer pioneered the use of Soft Magnetic Composite (or “SMC”), formed under intense pressure into segmented poles along the stator. Easier said than done. The company founder saw SMC’s possibilities before there were paying customers. The Tesla Roadster hit the road in 2008, while Woolmer was still working on his PhD. Processes, tooling and suppliers for these newfangled machines didn’t exist.

Formed into computer-designed 3D shapes, lightweight SMC replaces the complex slot windings of conventional motor designs. Short, flat copper windings allow direct oil cooling, Odling says, with no “buried copper” that oil can’t reach. Where a traditional motor loses power quickly under track-style stress, as windings heat up and electromagnetic resistance increases, these units can run continuously at much higher power levels.

“If you want a really fun EV, because of the power density we offer, and the ability to thermally recover much quicker, you could drive a car fast on track again and again,” Odling says. “Or optimize a battery for all-day touring range, in a car that’s still exciting on track when you want it.”

The company appears on the cusp of another breakthrough that has stymied engineers. In December, YASA revealed a prototype in-wheel motor with identical performance numbers, light enough to overcome the issue of unsprung weight for in-wheel designs. Its 1,005-hp peak translates into equally crushing regenerative braking capability, enough to downsize or even eliminate physical rear brakes, just like Formula E Gen 3 racers. Driveshafts are eliminated, and supporting structures can be lightened, in a cascade of weight savings.

YASA figures its in-wheel design can trim 440 pounds from current EVs, and up to 1,100 pounds with a clean-sheet design. The latter figure is enough to entirely offset the weight of today’s typical 75 kilowatt-hour battery packs, without even considering solid-state or other battery advances.

“You can change an entire vehicle architecture, get weight out of the axles, and really optimize how much battery you need,” Odling says.

YASA also revealed what it calls the world’s first dual inverter. The critical power electronics weigh just 33 pounds but can manage 1,500 kilowatts, or 2,011 horsepower. That power-to-weight ratio is a good 50-percent jump over today’s leading EV inverters.

Mercedes wisely took an early stake in YASA, and made the company a full subsidiary in 2021. Daimler, Mercedes’ corporate parent, is retrofitting a factory in Berlin to build up to 100,000 YASA motors a year. That follows a May opening of YASA’s new facility in Yarnton, U.K., with annual capacity for more than 25,000 motors.

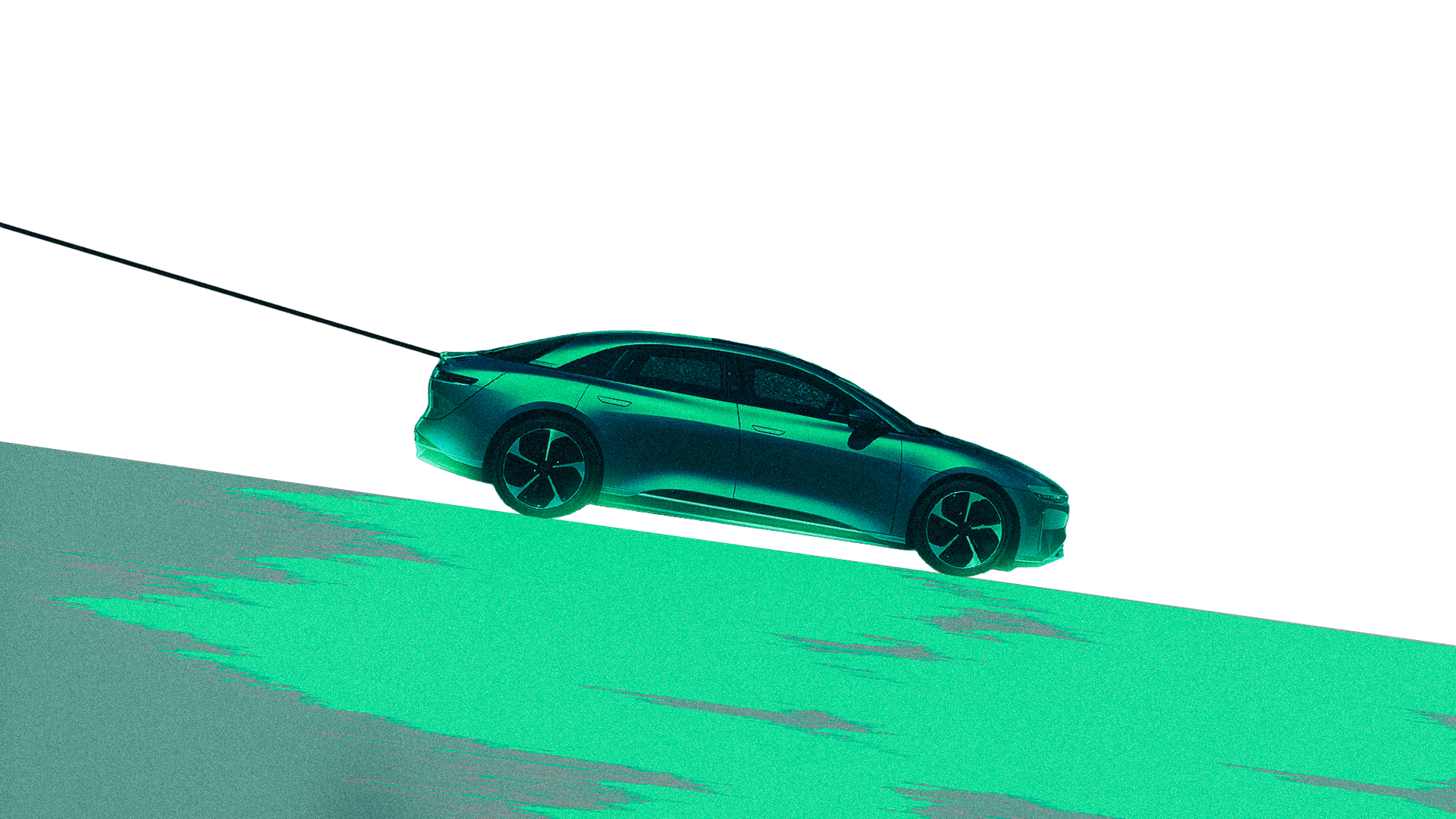

Thanks to its sugar daddy in Stuttgart, YASA units will find their way into a production EV for the first time. The Mercedes-AMG GT 4-door Coupe will integrate three motors and surely generate more than 1,000 horsepower. Offshoots will follow on a new AMG.EA electric platform, including a high-performance SUV.

The GT Coupe is already rolling around the Nürburgring in camouflage, and getting a handsome marketing boost from Brad Pitt and F1 pilot George Russell, who paired up for some Las Vegas drifting.

The GT Coupe itself descends from a 1,360-horsepower Mercedes-AMG GT XX prototype that set dozens of EV endurance records. Circling Italy’s Nardo circuit at 186 mph, the GT XX covered 3,405 miles in 24 hours, beating the XPeng P7 by nearly 1,000 miles. A pair of GT XX’ proceeded to travel

the equivalent of the earth’s circumference in 7.5 days, over 24,902 miles. The time included charging stops at a sizzling 850-kilowatts. That pace will translate to YASA-powered production models, on par with China’s leading-edge BYD models and “megachargers” that can juice an EV in about five minutes flat. If you’re looking for electric speed, that’s a key part of the equation.

Bottom line? As the retired Corvette Chief Engineer Tadge Juechter told me, as his team developed the C8 Corvette, E-Ray and ZR1X, electricity is no longer something to fear. (If anyone is stubborn about change, it’s a traditional Corvette buyer). Electric sports cars are coming, more slowly than we might have expected. They’ll suffer growing pains like any new tech. But with the world’s performance leaders all working the problem, including at the pinnacle of racing, it’s just another engineering challenge to overcome.

We might also be celebrating this moment in automotive time. Around the world, people remain free to drive their ICE cars and classics, to tuck them away, show them off or pass them down. At the same time, the Venn diagrams of gasoline and electricity are converging to create a greener, golden age of performance. Enthusiasts can bask in its glow, or get out of the way. Because your ICE car is already being passed.

Recent Posts

All PostsFebruary 27, 2026

February 26, 2026

February 25, 2026

Leave a Reply