Mystery Machine

January 5, 2026

Brett Berk

Packard pioneered putting V12s in cars in 1915. And this unique Packard “Twin-Six” singlehandedly encompasses everything about the early luxury car market in Detroit

Brett Berk discovers an unusual and previously unknown Packard in Detroit.

Packard was founded as an ultra-luxury automaker at the tail end of the 19th century. Though originally headquartered in Indiana, it soon moved operations to Detroit, the industry’s epicenter. In an era when the least expensive cars cost under $400, and a mainstream “Curved Dash” Oldsmobile was around $650, Packard positioned itself far higher, concentrating on wealthy individuals who would pay over $2500 for a car of superior quality and appointments. Its only real domestic competitors, according to concours judge, author, and curator Ken Gross, were the other members of the so-called “Three Ps of early luxury cars: Packard, Pierce-Arrow, and Peerless,”

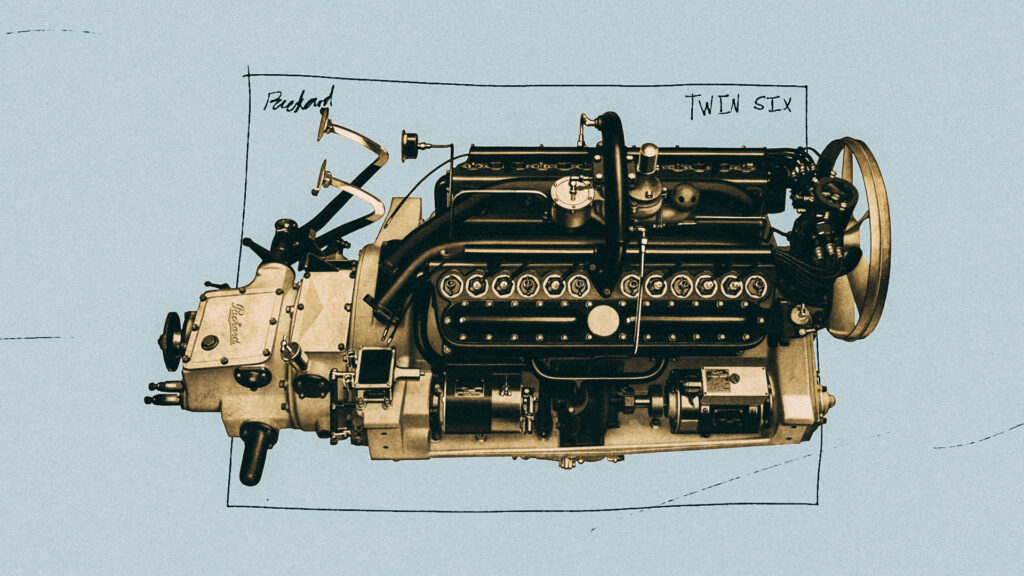

To elevate the brand within this elite cohort, Packard sought distinction under the hood. 12-cylinder engines had been used in maritime and early aviation applications, and intrepid individuals had shoehorned them into experimental or racing cars. But with its Twin-Six line of vehicles of 1915, Packard was the first automaker to employ such a design in a production automobile. Displacing 424 cu.in. (6.9 liters) and producing 85 hp, the 60-degree V12 was a paragon of smooth operation, taking the inherent rotational benefits of a straight-six and doubling it.

“Cadillac was doing a V8 fairly early on and so they kind of leapfrogged it,” says Gross. “Given that they were in the prestige automobile field, it made perfect sense for them to have an engine no one else did. Having a V12 gave Packard bragging rights because they were first to do so.”

The inherent limitations in Brass Era cars provided clear incentive for the development of such a motor. “Multi-cylinder engines were big and torquey,” says Gross. “You didn’t have automatic or synchromeshed transmissions yet. So, if people wanted to do minimal shifting—whether your chauffeur drove or you did—they could start in first gear, and very quickly shift into top gear. Certainly a twelve-cylinder engine would do that.”

The Twin-Six was a resounding success for Packard. The company sold them between 1915 and 1923, in two lengths— wheelbases of 125” or 135”— and a broad range of off-the-shelf or custom body styles from two-door roadsters to stately limousines. Over 30,000 were produced. This, despite the fact that the cars cost between $3000 and $5000—nearly $100,000 to $160,000 in today’s money. They remain valued exemplars of their era’s top tier. Sites like Packards Online maintain a registry of 174 existing Twin-Six cars in various body styles.

I know this in part because I recently fell down a rabbit hole trying to uncover the story of one particular Twin-Six. The origin of my quest can be traced to my (equally) car-obsessed younger brother Derek and his wife, who recently acquired her stately childhood home in our hometown of Detroit’s Boston-Edison historic district. The mansion was built in 1912 by Joseph Mack, a printer who had noted the auto industry’s need for catalogs and advertisements, and founded a successful and eponymous local press that undercut prices in the publishing center of New York. Other titans of industry also built homes nearby—Henry Ford and Ford VP James Couzens, as well as Walter Briggs and a few of the Fisher Brothers, all of whom founded businesses that constructed car bodies.

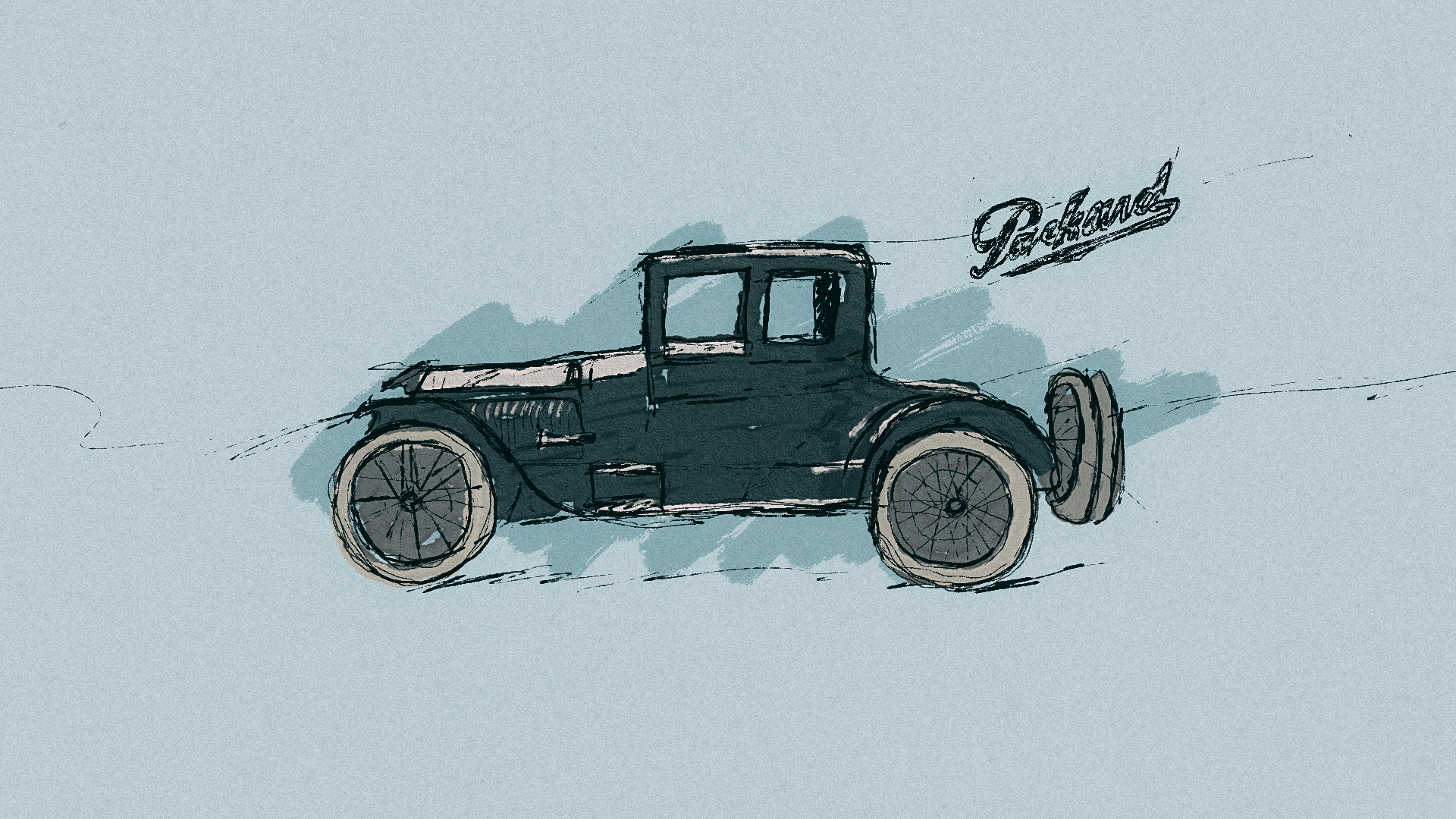

While Derek and his family were working on sourcing materials for restoring their imposing Manor, a member of the neighborhood’s architectural history society provided them with a photo of the house from 1916. Parked in front is this sporting 1916 Packard 1-25 Twin-Six Coupe, the rarest of the 3600 models built that year on the shorter 125” wheelbase chassis that gave this model its name. Packards Online does not have a single coupe in its database. Because of its limited practicality, not that many were made.

“A coupe like that wouldn’t have been a wealthy family’s main car. In those days you bought a sedan or an open touring car—though in Detroit, the weather would preclude that,” says Gross. “I’ll bet the first owner was a wealthy professional, and this was their second car.”

We initially thought the car must have belonged to Mack, and he commissioned the photo to show off his success, automotively and residentially. Digging deeper, however, I discovered that this photo was part of a trove of over 100 images, all in the collection of the Detroit Public Library. It features various vehicles—custom body types, including hearses, delivery vans, buses, and firetrucks, as well as limousines, convertibles, sedans, and landaulets, from a range of local brands including Hudson, Cadillac, and Dodge—made in 1916 for the coachbuilders Erdman-Guider. E-G was part of a tangled web of interrelated (and intermarried) German/American family businesses that traced their roots to the carriage trade of the mid-19th century, and became extremely prominent in Detroit with the rise of the automobile.

The problem was, few records existed of Erdman-Guider, and no experts had ever seen or heard mention of an Erdman-Guider bodied Packard. “It just doesn’t appear in the record,” says Gross, after consulting his extensive research library, and those of peers and colleagues. Tim Martin, the Packard Club roster keeper for Twin-Sixes, told me, “This photo is the only one I’ve seen that shows an Erdman-Guider body on a Twin-Six. Whether it was the only Erdman-Guider bodied Twin-Six is an interesting question.”

According to contemporary newspaper clippings I discovered in the Detroit Public Library, Erdman-Guider was formed in 1915, so this array of images and vehicles would have been from early in the firm’s existence, perhaps intended to show off its capabilities. Its first factory was right where the Renaissance Center stands in downtown Detroit today (as it grew, it opened a satellite factory in Saginaw, Michigan.) These facilities were responsible for the bodies of the first closed Cadillacs—in wood, and then in aluminum and steel—and ended up specializing in high end custom-bodied passenger cars and limos, especially hearses and ambulances.

My brother and sister-in-law’s house, and those of their neighbors, appear repeatedly in this tranche of DPL images, leading me to believe that maybe they were part of some project of Joseph Mack’s printing empire. Perhaps he regularly used his neighborhood as a backdrop for catalog shoots? I have not been able to find any evidence that he did this for Erdman-Guider, but the imprint of the Joseph Mack Printing Company is all over a huge range of catalogs for early automakers, many of which are in the collection of the New York Public Library.

Another element in the Detroitness of this story, the headquarters and presses of Mack’s company were housed in a new building he commissioned from pioneering industrial modernist Albert Kahn—the so-called “Architect of Detroit.” In addition to building the Ford River Rouge factory, the original General Motors headquarters, a number of historic homes in Boston-Edison, and the core buildings in the University of Michigan’s Ann Arbor campus, Kahn also designed the local Packard factory. Mack press was right where the Detroit Tiger’s Comerica Park now stands downtown.

Mack exited printing business in the mid 1920s to focus on real estate development; he was one of the major developers of the tony Detroit suburbs of Birmingham and Bloomfield Hills. Like many coachbuilders, Erdman-Guider expanded and contracted in the 20s and 30s, before ceasing to exist toward the middle of that decade, due to the general death of American coachbuilders brought on by the Depression. By continuing to innovate, Packard outlasted its Classic Era competitors. But like many independent automakers, it succumbed to industry consolidation in the post-war era. It merged with Studebaker in 1954 and produced its last vehicle in 1958.

However, the V12 engine continued to exist. Less exclusive luxury brands like Cadillac and Lincoln took it up in the 1930s. Packard kept itself in business as long as it did by producing more than 50,000 V12 military aircraft and marine engines during WWII. But the configurations perhaps found its apotheosis in Italy after the war, when it began appearing in sporting road cars. “It may be apocryphal,” Gross says, “but Enzo Ferrari was quoted as saying that he was seduced by the song of a twelve-cylinder Packard engine he’d heard in Italy, and Ferraris for a long time only had V12s.”

A V12 is still a potent signifier. Ferrari and Lamborghini insist on the V12 howl as a heritage halo. Contemporary gas-powered Rolls Royces only offer V12s. Boutique manufacturers like Pagani and Gordon Murray Automotive worship at the howling V12 altar. And a V12 is wildly flexible. Aston Martin and Mercedes reserve V12s, respectively, for their most exclusive sporting and luxury cars.

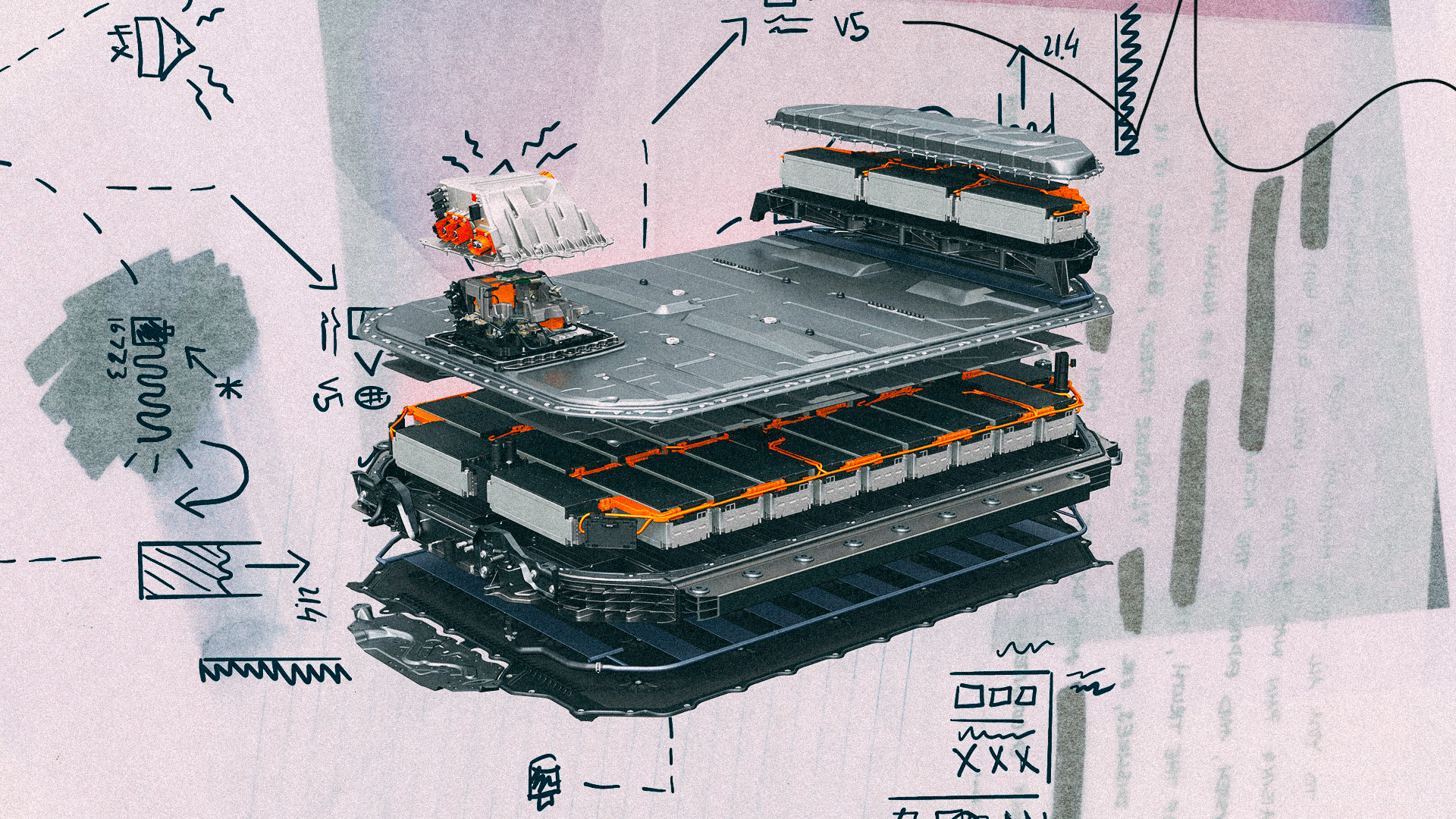

Notably, many of the V12s core characteristics—effortless torque, smooth operation, gobs of power in reserve—are also characteristic of electric vehicles, though EVs obviously don’t have the V12s mellifluous or muffled grunt. I have driven many V12s, new and classic, and even a few new and old 16s, but I have yet to hear the roar of a Packard Twin Six. If you have one, let me know in the comments and maybe I can take it for a spin and report back.

Recent Posts

All PostsAlloy

January 30, 2026

Peter Hughes

January 29, 2026

January 29, 2026

Leave a Reply