Unboxed

January 29, 2026

Alex KiersteinHow an EV battery is packaged within a car, it turns out, is almost as important as the battery itself.

Autocar in the UK has an excellent report on cell-to-body construction, an emerging technique for packaging EV batteries within a vehicle that does away with the battery box. I encourage you to go read the whole thing, but I’ll also note the report’s highlights and add some context.

It’s fascinating because the cell-to-body solution seems so obvious now that companies like BYD are out there doing it. But as Autocar notes, Europe is behind. Most of its EVs still use separately produced battery boxes. A large, well, literal box made out of aluminum houses the batteries, which are generally arranged in modules of a certain number of cells. The battery box protects the batteries, particularly from intrusion from below, but also contains the temperature control system and serves to contain (somewhat) things in case of a “thermal runaway event.” In other words, the sort of catastrophic, violent fires that happen when a lithium ion battery turns into an incendiary device.

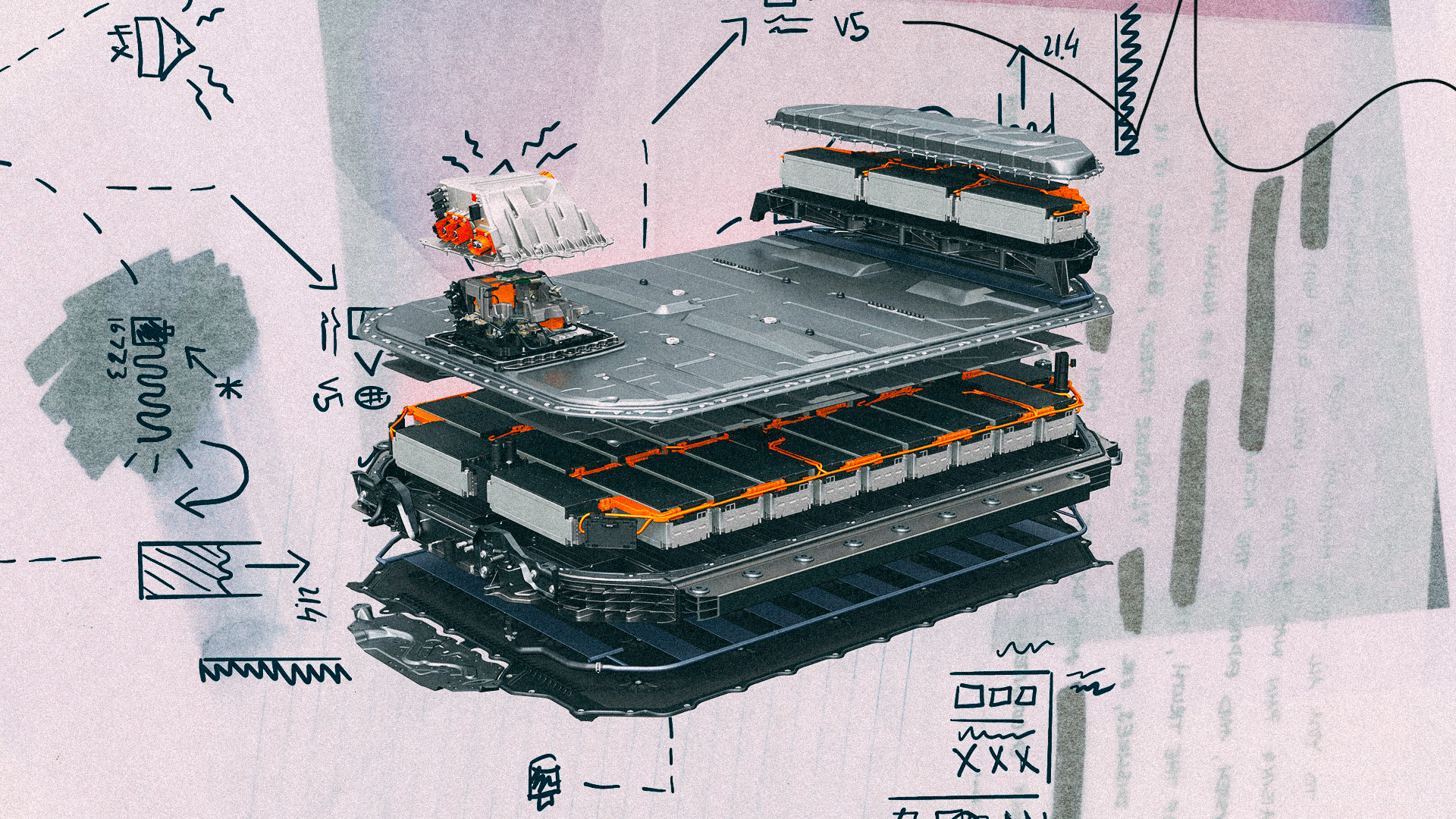

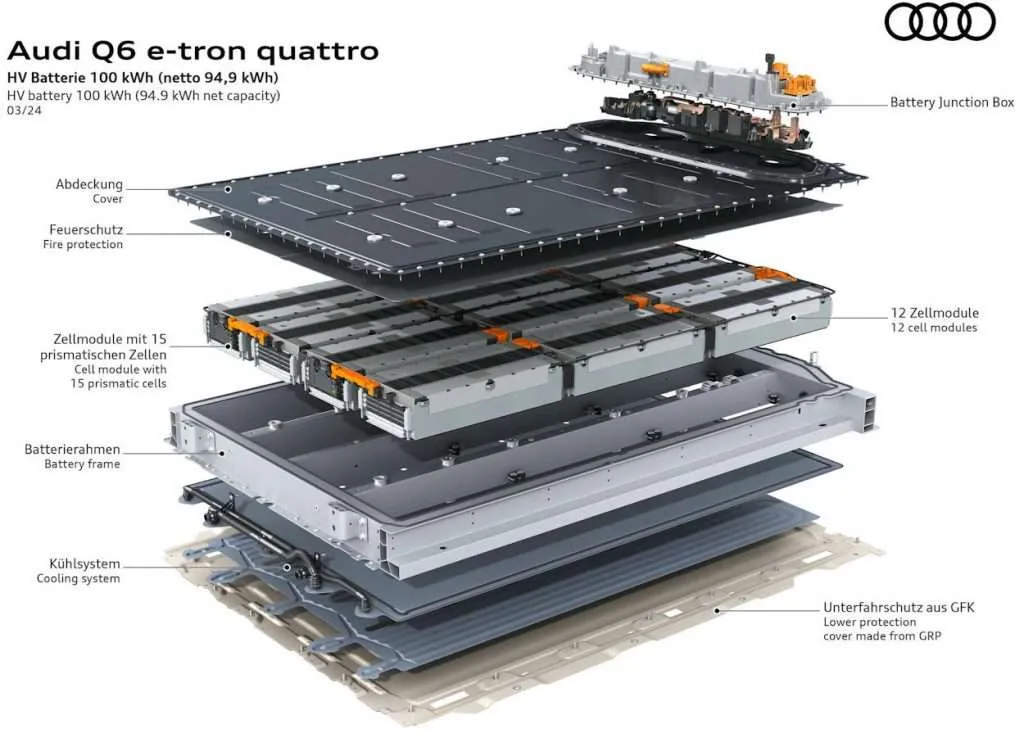

But just looking at a “cutaway” of a traditional EV battery’s construction (in this case, an Audi E-Tron battery, but typical), you see how much material, how much complexity, is involved. Not only is there a protective undertray—something that both traditional and cell-to-body vehicles use—there is also a perimeter frame, an internal frame to hold the modules in place and provide some structural protection, trays to hold the battery modules, and the material that is placed around the battery cells to create modules.

That is a LOT of material. As Autocar points out, the solution is to radically simplify, and this is an area in which the Chinese EV manufacturers are way ahead—the BYD Seal is one of several vehicles that use the cell-to-body tech. The first step was to eliminate the modules and create batteries with a large, uninterrupted group of cells—cell-to-pack. The next step was to eliminate all of the extra aluminum and plastic bits that framed and supported the battery, engineering that structure into the vehicle.

Using the chassis as the perimeter frame and top cover means all you need to do is add the battery pack and its bottom cover. It also means that removing the battery, for service or battery swap type charging, is much simpler. It’s not contained within a massive structure that has to be removable, with all the compromises and fasteners and extra manufacturing complexity. You just stamp the unibody differently, making room and structure for the battery.

And also, isolation and protection. Sure, the battery isn’t fully contained by a box, but that doesn’t mean your ass is literally in the line of fire. You have the vehicle’s floor, which can now be designed to be the battery top cover. Instead of the floor AND a battery box lid.

Makes a lot of sense. But it also requires designing the vehicle specifically for the pack, and having all the upstream suppliers on board to produce packs to this design. And Europe, as is the thrust of the Autocar piece, ain’t there yet. Not by a long shot. Most of its automakers are still using cell-to-module packs, although Autocar notes that Renault is using a smaller number of modules in the 4 and 5 BEVs—a step towards cell-to-pack.

Read the Autocar piece to get their take on the European automakers’ current strategies and future plans.

It must be noted that the Tesla Model Y uses cell-to-body tech, as does the much more recent Volvo EX60. And Porsche utilizes a hybrid approach, which you might call module-to-body; the battery box is eliminated but there are still modules. The advantage to this, I suppose, is that individual modules can be removed and repaired or replaced.

Cell-to-body construction has a few downsides, as the mention of repairing individual modules may have you wondering, “if all the cells are just arrayed inside a single pack, what happens if an individual cell goes bad? Do you have to replace the whole battery?” Maybe. It depends. I don’t have a good answer for you, but it’s a concern among producers. The batteries also must be handled differently (consider how they must be supported in transportation without a protective battery box or module structure) and, as you can probably guess, there’s a higher potential for a fire to spread in the pack.

All of these things are engineering and design issues, and are certainly solvable. But where cell-to-body producers are compromising and what they are prioritizing are still being sorted out.

My take is that it makes too much sense not to go this route. The economics of moving battery retention and protection into the unibody—which is a retention and protection structure by design—are undeniable. Perhaps we’ll also see this tech in hybrids, as models with no non-hybrid options can simplify things by incorporating the box into the structure, too.

Last advantage: fewer individual components means less overall weight, which is the same as increasing energy storage density. More bang for the electron.

Efficiency is cool. Are you sold on cell-to-body yet? I am.

Recent Posts

All PostsAlloy

January 30, 2026

Peter Hughes

January 29, 2026

January 29, 2026

Leave a Reply