The Fix

February 2, 2026

Brett Berk

The Swedish-German emissions system fostered an era of responsible performance.

How Volvo’s Lambda-Sond Conquered the Malaise Era

“I think this is probably the first one of these I’ve seen in the wild that is running so nicely,” says James “Bailey” White as he leans over the harp string-like array of slender tubes in the engine bay of a 107,526-mile Volvo 245 wagon. “These do not like to sit because these fuel lines get all gelled up and the injectors get clogged and everything is either expensive or no longer available.”

The diagnostic and calibration specialist from Volvo’s tech outpost in Silicon Valley, should know. He worked as a Volvo dealer mechanic for eight years, and personally owns a handful of the rectilinear 240-series vehicles for which the brand is perhaps best known, including the 1990 wagon in which his parents brought him home from the hospital as a newborn.

But it’s not solely the early Bosch K-Jetronic fuel injection system that he’s admiring. It’s the oxygen sensor buried somewhere between the exhaust manifold and the muffler.

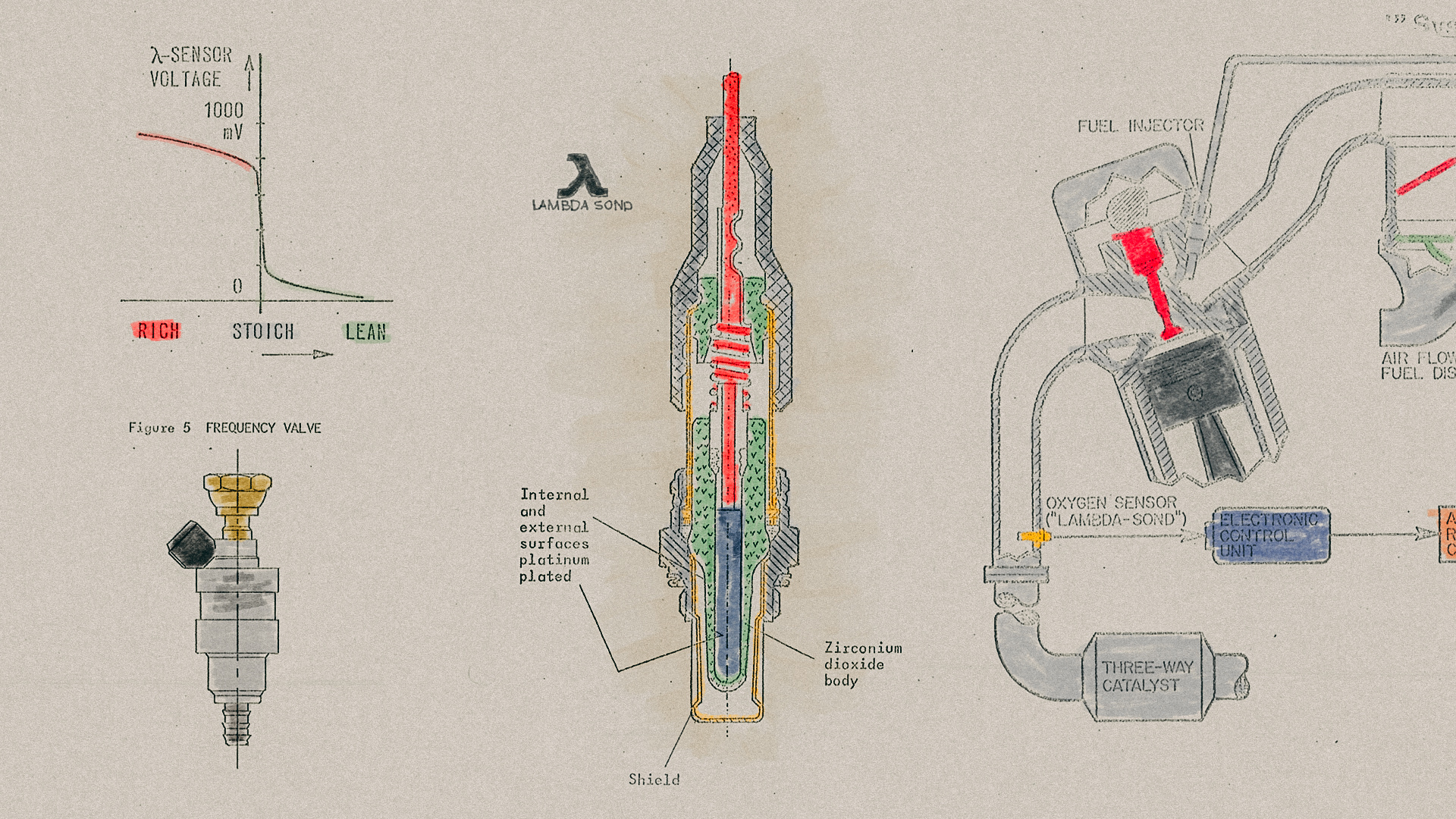

This little device, developed by Volvo in collaboration with Bosch in the early 1970s, became known by the trademarked name Lambda-Sond. (Lambda is the Greek letter that, in automotive engineering, represents the air-to-fuel ratio and Sond is the Swedish term for “sensor.”) And it was, remarkably, responsible for what Tom Quinn, the chairman of the California Air Resources Board in the Malaise Era called, “the most significant breakthrough ever achieved” in cleaning up automotive emissions. [Audi, Porsche, and VW were working with Bosch on similar systems in the same time period.]

It also allowed automakers to fit more powerful engines to vehicles of the era and still pass increasingly stringent emissions standards. “Having Lambda Sond allowed high performance cars to get into the hands of an average consumer,” White says.

So, how did this come about? And why was stodgy Volvo the first automaker to unlock the potential of producing engines that could run well under all circumstances, make more power, achieve increased fuel economy, and exhale less toxic exhaust?

The Backstory

The Clean Air Act of 1970 set comprehensive new federal standards to stringently regulate the release of toxic chemicals. In the five years after its enactment, it required a 90% reduction in automobile exhaust of harmful elements like lead, sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen oxides. Around the same time, strict new national fuel economy standards were adopted to decrease dependency on foreign oil.

The auto and petroleum industries had long been successful in fighting such restrictions. So, when they came into effect, these constituencies were hubristically unprepared. “They had to come up with quick solutions to meet emissions standards, and everybody had their own idea,” says White.

Some automakers, like Honda, crafted novel fixes. The Japanese company created its CVCC stratified charge engine, which pre-ignited a small, rich mixture of air and fuel, and used that to combust a larger, leaner mixture; it burned clean enough to pass emissions regulations. Others considered exiting the American market altogether. For Volvo, which sold nearly one-third of its annual production in the US, this wasn’t an option. And it saw the benefit of staying ahead of what it believed was bound to become a global regulatory issue.

Working from its new Technical Center in Sweden, the company explored a range of options, including rich and lean thermal reactors, alternative power sources, and various types of catalytic converters, which use noble metals like platinum and rhodium, and heat, to transform harmful byproducts into more benign ones. But because the targeted pollutants—NOx, CO, and SO2—were released in different quantities under different circumstances of combustion, it was difficult to find a solution that would achieve consistent results for all, simultaneously. This was especially true given the widespread use of carburetors, a somewhat blunt and arcane fuel delivery technology.

The Discovery

It was long believed that controlling the input—the quantity and mixture of gasoline—was the best way to regulate the output: the exhaust. As it turned out, the solution lay in reversing the equation, using the output to modify the input.

In 1972, Volvo engineers, working with a Bosch fuel-injection system, placed a sensor in the exhaust stream. This unit could then monitor the gases there and note the precise composition under which the catalyst best achieved its goals. When these conditions were met, the device could then signal the engine control unit to adjust the air-to-fuel ratio to maintain these conditions, those that were ideal for the catalyst’s operation.

This so-called oxygen sensor, which Volvo called Lambda-Sond, looked like a hollow spark plug, albeit one made of zirconium dioxide coated with platinum. It worked by noting differences in oxygen concentrations on the inside and outside of its cylinder, and sending an electrical signal—proportional to these differences—to the fuel injection system’s ECU. This computer controlled the fuel delivery valve, increasing or decreasing the pressure, as measured by flow-over metering slots in the fuel distributor.

“It’s completely mechanical,” White says. There’s really no latency because everything is mechanical and it adapts so quickly.”

Lambda-Sond only added $50 to the cost of a Volvo. And because it automatically adjusted fuel delivery for optimal emissions-reducing combustion under all circumstances—at all speeds, temperatures, conditions, and altitudes; when idling or driving at wide-open throttle—it eliminated the problems endemic in other systems, including complexity, inconsistent and awkward operation, added weight, reduced power, and diminished fuel economy.

In fact, when officially tested, Volvo’s system trounced the competition, overshooting the regulations. While California’s stringent laws permitted .4 grams/mile of hydrocarbons, Volvo’s test vehicles only emitted .2 grams/mile. While the regs permitted 9.0 grams/mile of carbon monoxide, the Volvo emitted only 3.0. And while 1.5 grams/mile of nitrogen oxides were allowed, it emitted just 0.2. And these weren’t the only gains. When the Lambda-Sond system went into production in the 1977 model year, the fuel economy numbers on the 240 increased by 5% over the similarly equipped 1976 model.

Repercussions

Cracking the code on how to exceed emissions regulations without flatlining power production created a template all automakers could eventually adopt. Turbocharging was one of the most prominent adaptations catalyzed by the new technology.

“Turbo cars existed before Lambda-Sond, all the way back to Chevy Corvair Monza and Oldsmobile Jetfire in the 1960s,” White says. “But if there’s no systems to monitor what’s going on, a turbo can kill your engine—you could get too much boost and shoot spark plugs out of the head. You have to have some sort of feedback. Lambda-Sond made it not as fraught or risky. Something was helping to twist the screws and make sure that your mixture was about where it needed to be.”

The system also had legs. “Though it came out in 1977, Lambda-Sond continued to pass new car emissions standards—which tightened every year—until 1994. Unchanged,” White says. “Because it was an adaptive system, they could use it exactly the same as it was.”

So, every time you enjoy the incredible performance capabilities of contemporary cars, give thanks to the stolid Swedish bricks from the Iron Cross brand.

Recent Posts

All PostsJamie Kitman -- Illustration by James Martin

February 6, 2026

February 4, 2026

February 3, 2026

Leave a Reply