Minima

The Nissan Maxima is dead and the Altima is caught in late-life lethargy. This would be an unfathomable state of affairs to anyone waking up from a coma that started in 2005. Of all the mainstream mass-market sedans, the Maxima and Altima had the strongest and most compelling pitches at the height of their appeal.

The Maxima became the 4DSC in its third generation—the four-door sports car. It recast a tech-heavy personal luxury sedan into a reasonably sporty (if slightly soft) front-driver. A healthy 160-hp 3.0-liter V6 and a crisp 5-speed manual, paired with a comfortable interior and a suspension tune that was more touring than slalom, struck a great balance for the sort of buyer it could actually attract. Sporty but not punishing. Comfortable but not wallowy.

While it didn’t have any overtly sporty pretensions, the Altima—which debuted just after the third-generation Maxima—also had a strong sales pitch. It was inexpensive, built in the states, and came with a powerful KA24DE engine (150 hp, when just a few years earlier 160 hp was enough to label a larger V6 counterpart sporty!) and a competent automatic (with an available manual). You could even fit an optional limited-slip differential, rare at the time and certainly not standard in mainstream non-sporty front-drivers even today.

Neither strayed much for several generations. The Maxima gained a VQ engine, first a 3.0-liter and later a 222-hp 3.5-liter in its early 2000s fifth generation. The styling, not as crisp and focused as the fourth-gen archetype, at least continued to visually convey the Maxima’s mission as Nissan’s sporty yet comfortable flagship.

The Altima emerged from a nondescript second-gen larval stage into, arguably, the most compelling mid-sizer of the 2000s. The third-generation L31 Altima debuted in 2001 as a crisp handsome car with (for the time) adventurously stylish taillights–clear outer elements with colored, round interior lenses. At the time, it was thought mainstream buyers would be repulsed by anything with adventurous styling; the Altima was considered daring even if it looks anodyne today.

And more importantly, the Altima got the VQ-series V6, in big-bore 3.5-liter guise. Making two-hundred-forty horsepower. The Altima was a sleeper in both conception and execution. And it was reasonably entertaining to drive, being slightly larger than its competitors but no heavier. The SE-R trim added a few visual and honest performance improvements to the mix, with (much) stiffer suspension and a few extra horsepower, finally backing up the Altima’s power-to-dollar appeal with a well-regarded legitimate sport variant.

It seemed as if, for a moment, Nissan could have redefined its entire sales proposition around a remarkable combination of attributes. The Altima was powerful, handsome, and potentially sporty. The Murano, just a year away and featuring remarkably compelling styling as well as a powerful VQ engine and additional crossover utility, bolstered the argument. Style, power, value.

Nissan approached this opportunity to boldly differentiate itself by carefully placing the Maxima on the ground like a rake and stepping on it. The Altima’s improvement and the Murano’s introduction significantly encroached on the Maxima’s core mission. Nissan responded by changing the Maxima’s mission, making the next generation more luxurious but still muscular, and also hobbling it with profoundly weird styling. Weird is a tightrope walk at best, and Nissan did not execute well.

The dilution continued. The seventh-generation Maxima was understated up front and completely anonymous in back. When the fifth-generation Altima emerged in 2012 with a Maxima-inspired rear, it didn’t emphasize the Maxima’s stylistic leadership, it instead reduced its appeal. Cover the badges up and attempt to identify the Maxima and the Altima by their rear fascias without using the “It’s the same image” image macro from The Office. It’s impossible—not literally, but metaphysically.

I think the seventh-generation is where the Maxima slid out of the enthusiast consciousness—less important for sales, but more important for media reaction and subjective buzz. With no manual transmission available at all, even just an on-paper offering with a fractional take rate, much of its theoretical appeal evaporated. What was it other than just an upscale Altima? Why not simply option up an Altima to a similar spec for less? Or, perhaps more pertinently, why not sit up higher in a similar mechanical package with better styling and all-wheel drive?

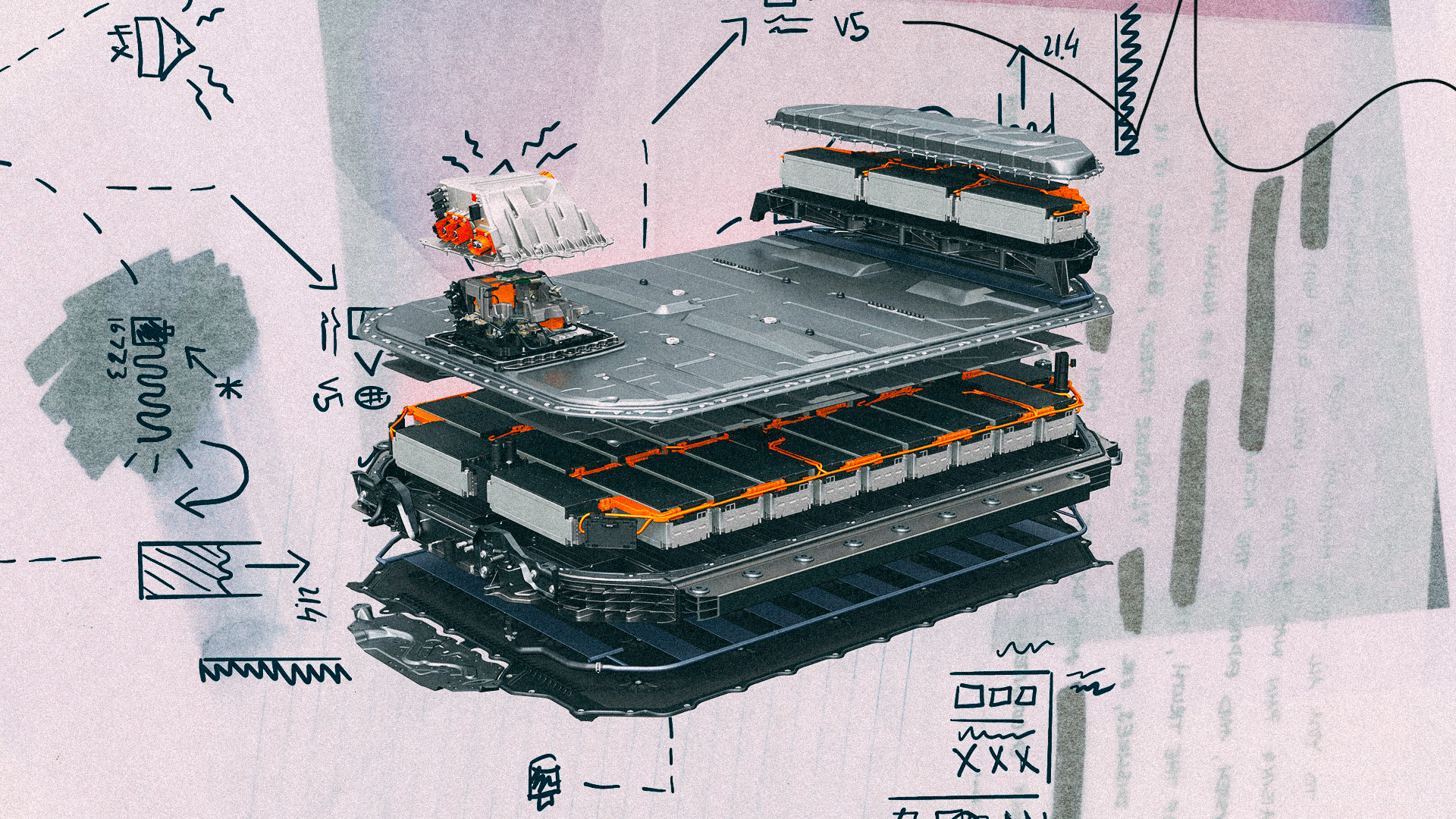

The Altima was not yet lost, although Nissan’s Vmotion corporate styling language blended the Altima (and the rest of the Nissan model range) into a muddy aesthetic puddle. The company had just introduced the VC-Turbo variable-compression engine tech in a few Infiniti products, and on paper this is exactly what could have elevated the Altima (and, perhaps, the Maxima). Innovative, unique, performance-enhancing while also improving consumption and emissions. Like the notably stout KA24DE and the grunt of the VQ35DE, a well-developed VC-Turbo might give the Altima a high-profile hardware advantage.

The VC-Turbo underdelivered, unfortunately, and lingering questions about its overall reliability dog the vehicles it is currently found in. The Altima dropped the complicated engine for the 2025 model year, leaving only a nondescript 2.5-liter naturally aspirated I4. Naturally, this led to chatter that the Altima might soon follow the VC-Turbo into the void.

There was, in my mind, a consistent and worthy case that the Altima could have made to consumers. Better than average power—gutsiness, muscle—at a better-than-average price point. That is a digestible sales pitch, and one that you can see the RAV4 Hybrids making in recent years with some success in a different niche. The Altima might not have needed to evolve into a crossover to survive, but given the addition of all-wheel drive in recent years, it might have moved into an adventure-oriented space as a fastback Outback or Crosstrek competitor, giving the company some sorely needed lifestyle vehicle credibility without too much overlap with the Rogue and Kicks.

The Maxima’s alternate history is less clear to me. The Maxima only briefly matched the promise of its branding. Perhaps it’s a testament to the appeal of that 4DSC pitch at that moment in time that enthusiasts even mourn the Maxima nameplate today.

Putting myself in that group, it’s also worth understanding the ways in which the enthusiast mindset does and does not move the levers of product development. Our voice is much larger than our actual economic leverage, and enthusiast desires often conflict starkly with more influential interests. Dealership franchise owners, for example.

Sometimes a company guides its consumers. Ergonomic controls designed by behavioral scientists; the automaker and its experts have leveraged the scientific process to lead you to an interior with benefits that must be articulated to you proactively. Like broader cultural trends, corporate focus shifts. We’re in a moment in which automakers seem to be chasing a prototypical consumer yearning for both novelty and also comforting rationality.

It’s why model naming schemes are revised when the old one no longer tracks; the notion that the consumer wants to know which one is “the best, the most” at a glance. It’s why most models within a brand’s range no longer have unique styling; instead, it’s a common corporate design interpreted in several sizes and variations. And it’s almost certainly why physical control inputs have been largely replaced by capacitive and touchscreen interfaces, despite solid evidence of their detrimental effect on driver focus.

If Nissan is chasing its forward-looking consumer archetype, which I’d argue it is and has been for several model cycles, the decision to drop the Maxima after the 2023 model year makes sense. And unlike the Altima, I have difficulty imagining how the Maxima’s form factor could evolve in a way that benefitted Nissan on the whole. But I also can’t help but feel that if Nissan had been able to stave off the Maxima’s identity crisis until the present, the easiest possible differentiation might have been to give the Maxima a high-performance hybrid all-wheel-drive system.

Changing the model’s trajectory would have required a clear vision and at least two product cycles—and Nissan’s financial troubles, executive drama, and internecine conflicts between Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi Alliance members didn’t help.

At this time, there’s no clear indication of the future that the Altima might have. If it merely continues on, coasting as many older Nissan models do, it may follow the Maxima into oblivion eventually. Know that it didn’t have to end like this. No nameplate is sacred, but Altima and Maxima used to mean something. The slow hollowing out of that meaning wasn’t just an avoidable tragedy, it was an opportunity squandered.

One response to “Minima”

-

A nice chronology, but I will take issue with your point about, “Neither strayed much for several generations,” i.e. the Maxima’s fourth and fifth gens. The fourth-gen Maxima (1995) was a fatal blow to the idea of 4DSC, due to necessary cost-slashing in the wake of the Japanese economic bubble bursting and the currency-exchange crisis of the yen endaka. Nissan was saddled with the already developed (and while lovely, expensive to amortize) VQ engine series to replace the VG. That meant decontenting ran amok on the rest of the car – the most damaging of which was replacing Maxima’s independent rear suspension with a cheapo beam-axle-Panhard-rod combo. What had been one of the best-handling and supple-riding sports sedans on the planet was now plagued with terminal understeer and a floaty ride on a much-longer wheelbase. The enthusiast audience for a 4DSC immediately sniffed this out. Ironically, the 1995-2000 era was the best-selling for Maxima, though a closer look shows this was due to a sharply rising percentage of rental-fleet sales to deplete rising inventories forced on it by Japan. The 1999 major-minor edition was essentially a sheet-metal refresh, as Nissan was drowning financially and couldn’t afford to make engineering changes. Nissan tried to rescue this miscue with the 2004 redesign, but the damage had already been done with enthusiasts. The 2004 edition was when Maxima began sharing a platform with Altima – which brought its own set of problems.

Recent Posts

All PostsAlloy

January 30, 2026

Peter Hughes

January 29, 2026

January 29, 2026

Leave a Reply