The Roman Way

November 7, 2025

Alex KiersteinRome projected economic and military power using a system of roads that is surprisingly poorly understood.

There are many cunning and ruthless ways to control an empire, and Rome perfected most of them. The Empire out-produced and out-competed its enemies economically using slave labor. It ruthlessly crushed revolts to create a lasting deterrent, and pointedly threatened smaller entities. “That’s a nice little kingdom you’ve got there. Shame if something happened to it.” Often, the threat of Roman military intervention was enough to create a beneficial result—manipulative diplomacy, which is the scholarly way of saying blackmail by threat of sacking.

Occasionally the Empire weaponized its remarkable engineering talents. Its road network, stretching across the Empire from Hispania to Roman Syria, is famously durable. I’ve seen them myself, in Caesarea, dating from the time of Herod the Great.

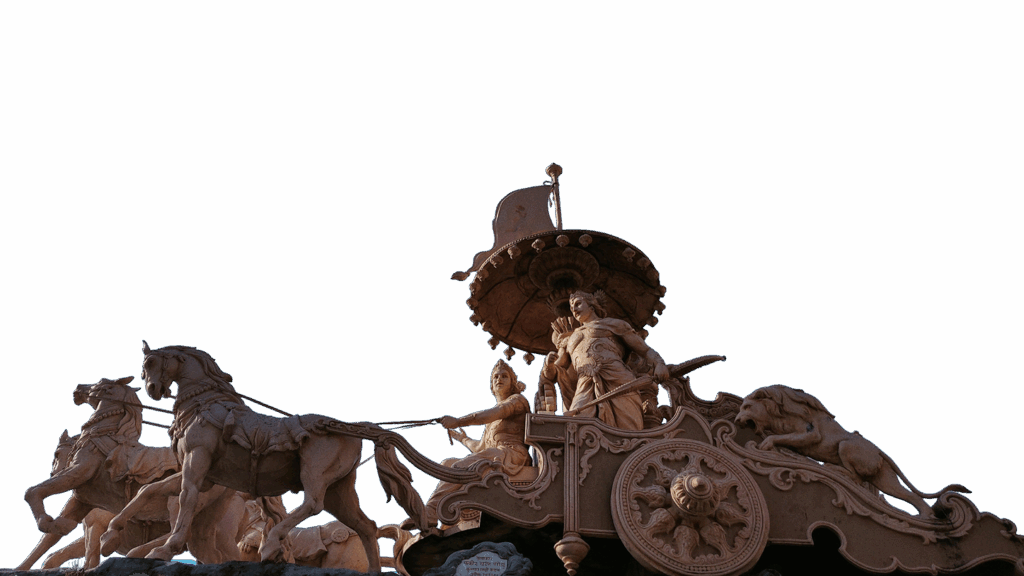

One reason for their longevity is the hard-assed attitude that led to their exacting precision. Romans did not do half-measures. Elsewhere in Judea in the decades after the construction of Caesarea, a group of extremist rebels and assassins (so we’re told, by sources we’re not fully able to trust, but so it is with history) holed up on a desert mesa known as Masada. With access to the top only by narrow paths that dangerously exposed attackers, it seemed like as good a place as any to equalize things with the overwhelming might of Rome.

The Romans did not simply lob a few ballista bolts at the Sicarii and pack it up. They constructed extensive stone camps, essentially modular military villages, to settle in and methodically build a monumental ramp up the hill. Some scholarship says that this enormous earthwork took only a month to complete, and then they marched up it and—possibly—slaughtered everyone on top. Or those on top, according to legend, took their own lives. The truth of the matter is, Romans did things to their fullest extent.

Like everything concerning the greater Empire, its provinces and hinterlands included, the scale of this road system is monumental. And, surprisingly, not as well understood as you’d think. Sure, the main roads are well-documented. The ones with the large blocks, cut with uncanny precision, with those deep wagon ruts that make onlookers wonder just how long it takes an iron-tired wagon wheel to grind away just a millimeter of stone, those are understood. But much of the broader network is not.

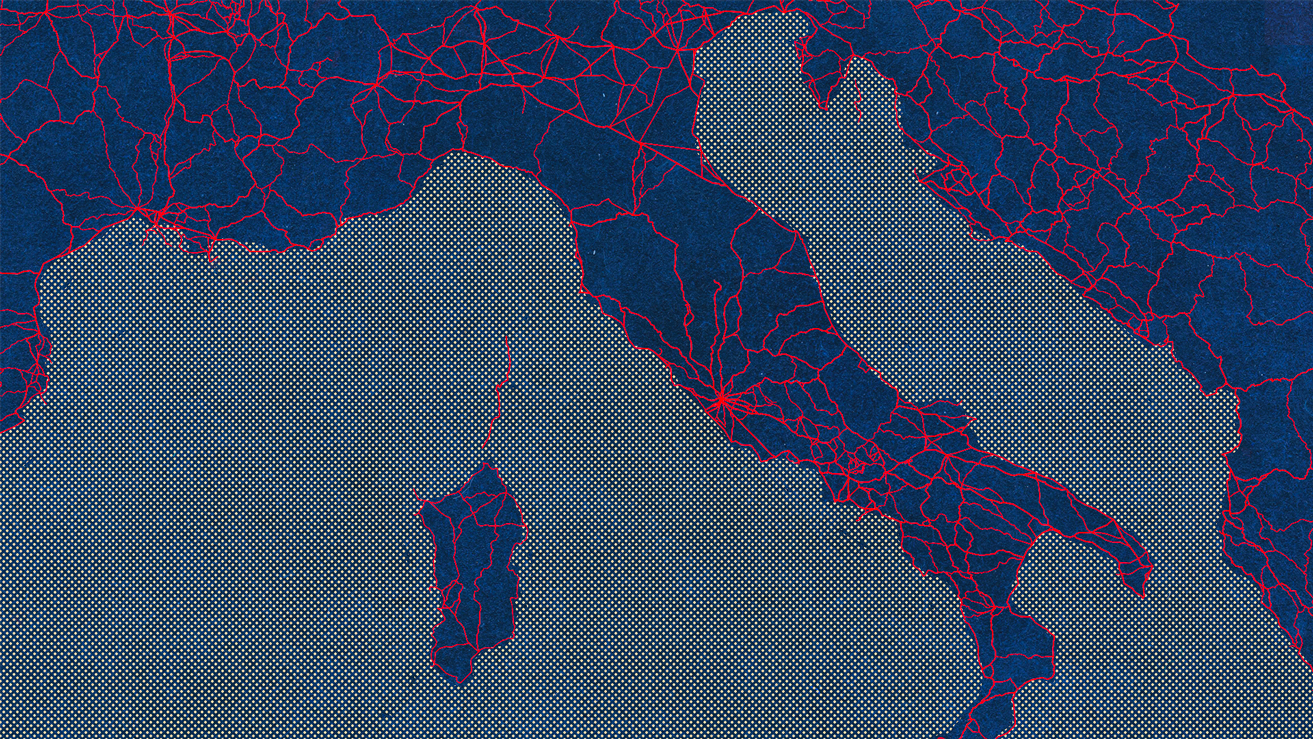

A recent metastudy attempts to put some actual numbers to this, and they’re honestly shocking to me as a casual student of history. The researchers compiled the sources, physical and historical, and came up with a total road network length of about 185,900 miles.

Not 1,859 miles. Just under one hundred and eighty-six thousand miles.

And to my amazement, of this, much of it is known only from nonphysical sources. Historians know a road connected two places in the Empire, let’s say, and there are multiple sources in the histories, records, and other nonphysical evidence for the road existing. But modern scholars don’t know exactly what route the road took. In other words, no one in modern times has seen the road itself, or at least hard evidence of its existence. Nor has anyone adequately collated the data in a way that allowed for anyone to fill in the blanks, argue the study’s authors.

The novel part of the study is an extensive search of other sources of information about the roads. The researchers mapped out the known roads and those presumed from historical sources, then compared them to modern and historical topographical maps, as well as satellite and reconnaissance imagery. They then digitized this all to give a more comprehensive, interactive view of the Roman road network at its greatest extent in roughly 150 CE, but also includes pre-Roman roads that were still used by Romans and modern roads that follow known Roman road routes.

It’s a remarkable way to visualize and interact with the data, and should be a boon for future researchers interested in exploring the flow of trade, war, and people throughout the Empire. The visualizer is called Itiner-e, and it’s free to use. Actual researchers can download the dataset itself. The authors of the study and the Itiner-e tool recently published an article in Nature detailing their findings and methodology, which is worth exploring if you’d like to learn more.

And you should. For Europeans, Roman roads are sometimes literally the foundation of their modern transportation network—the roads underneath their roads.

Recent Posts

All PostsAlloy

January 30, 2026

Peter Hughes

January 29, 2026

January 29, 2026

Leave a Reply