New Discipline

October 8, 2025

Brett Berk

Recently unearthed sketches provide a look at the early days of car design.

Recently unearthed sketches provide a look at the early days of car design.

Newly-discovered sketches from the genesis of car design

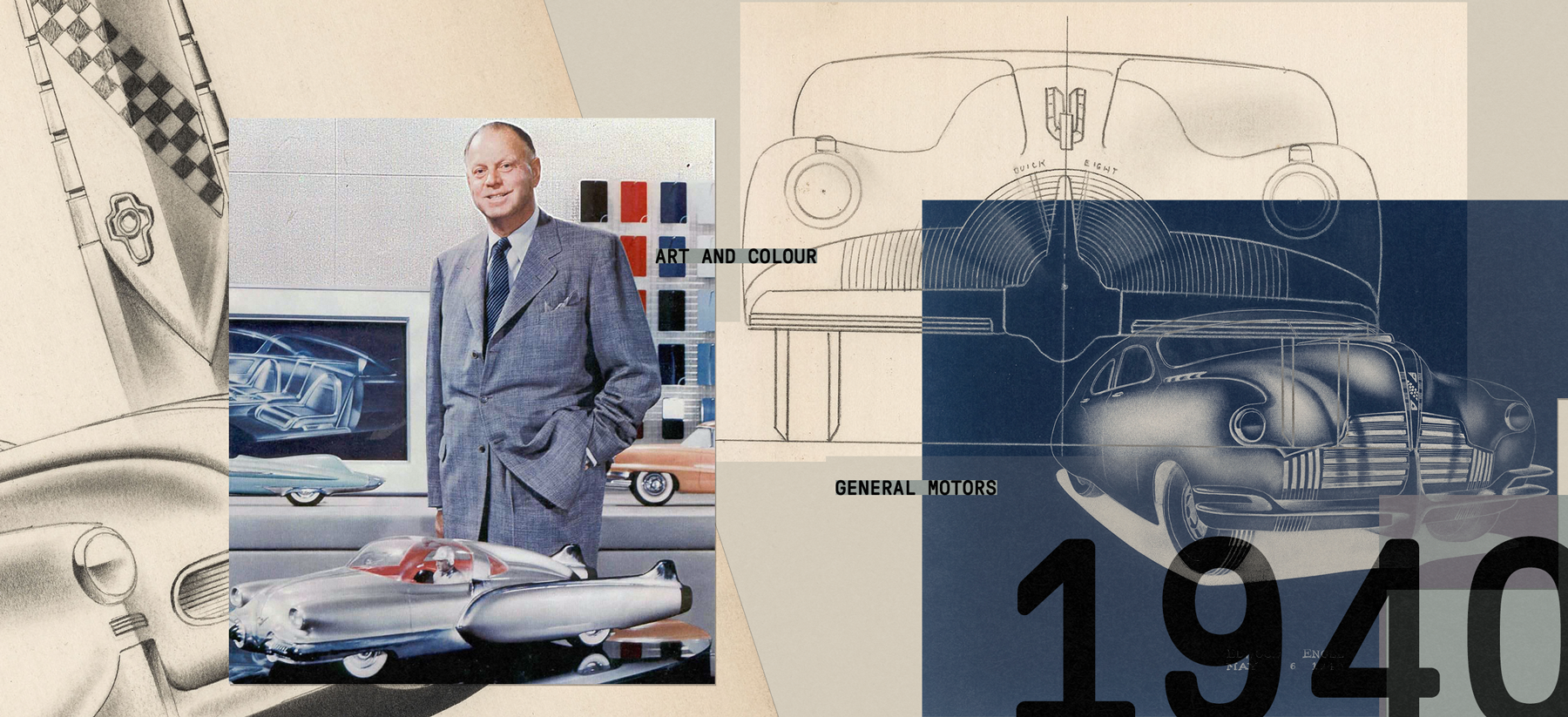

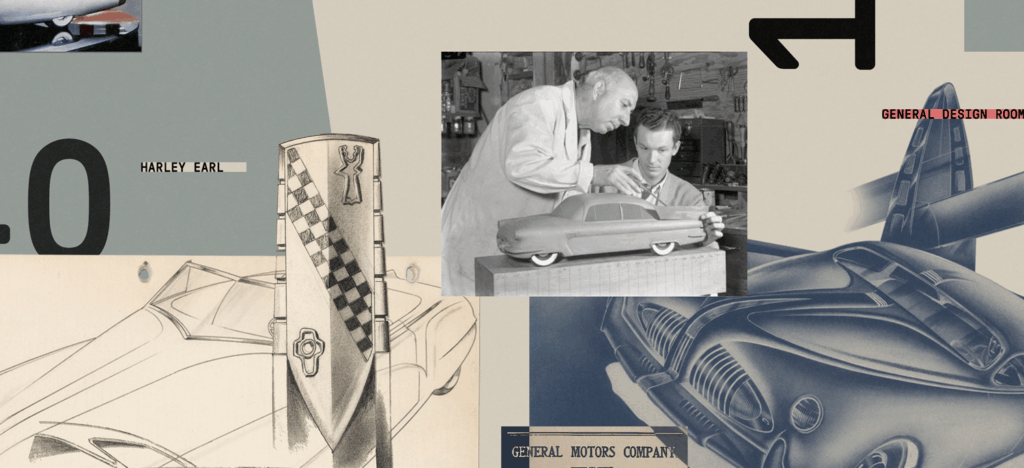

Harley Earl arrived at General Motors in 1927 as its first styling director, heading up the new “Art and Colour Section.” The 34-year-old Californian had come to the attention of GM president Alfred Sloan through Earl’s extravagant work customizing Cadillacs for Hollywood elites at his father’s Los Angeles coachbuilding shop. On this basis, and a successful test design for the 1928 LaSalle, he was given the daunting task overseeing the creation of all models within GM’s famed “ladder of brands”—from Chevrolet up to Cadillac—as well as GMC trucks.

This brought a broad set of challenges. First, automotive styling was not seen as relevant. Up until that point, the appearance of the growing category of mass-market cars was generally dictated by engineers, in a purely functional manner, with some distinctive adornment acting as differentiation. In contrast, the artful design of top-tier vehicles—Packards, Cadillacs, Duesenbergs—was handled by coachbuilders, who could create off-the-shelf or highly customized bodies as dictated by individual clients. Executives and engineers at GM referred to Earl’s new department, derisively, as “The Beauty Parlor.”

Second, and more important, because Earl was essentially creating a discipline, there was no pipeline or institutions for training new automobile stylists. “At that time there wasn’t such a thing as transportation design,” says Christo Datini, manager of General Motors’ design archives. “You couldn’t go to college or trade school and study that.”

To meet his needs, Earl had to get creative. When he was staffing his organization, Datini says, he recruited advertising and magazine illustrators. He took in engineers trained on big blackboards. And he hired folks from existing coachbuilders, like Thomas Hibbard from Carrosserie Hibbard et Darrin in Paris. “But there was no way to find new talent, to train new talent, and to evaluate that talent, all three in one,” Datini says.

To scale up, Earl decided to create his own proprietary school and curriculum. So, in 1938, he founded the Detroit Institute of Automobile Styling. Right up the street from the similarly-named Detroit Institute of Art on Woodward Avenue, and housed at General Motors’ headquarters, the DIAS was funded entirely by GM with the goal of nurturing the first generations of automotive design talent. The tacit understanding being that the best students would be hired by GM.

“It was a place to orient potential designers, to bring in potential new hires and kind of teach them the ropes,” Datini says. “And if they made the grade, they would be moved into a studio, and perhaps advance. And if they didn’t, they’d find their way back onto the street, or to other automakers. It was a way to evaluate talent.”

This was extremely relevant for Earl because, according to Datini, he had strong ideas and instincts but couldn’t necessarily execute. “He knew how to orchestrate, and he knew what he wanted—he had a singular vision and he could guide,” Datini says. “But he was not known to communicate well in drawing. So he was looking for people to help him realize that.”

The Institute became a nursery for future talent, and a means for Earl to test and refine ideas. It eventually expanded into a correspondence course, and even a national design competition among teenagers. This is evident in GMs’ archives, which are, according to Datini, stocked with myriad photocopies or digitized scans of student work, mainly gifted, unsolicited, from descendants of designers who have retired or passed away. “We want to create our digital record, and we’re really looking to create a reference point, a library for designers and researchers,” Datini says. “We’re not necessarily looking to enhance the physical collection.”

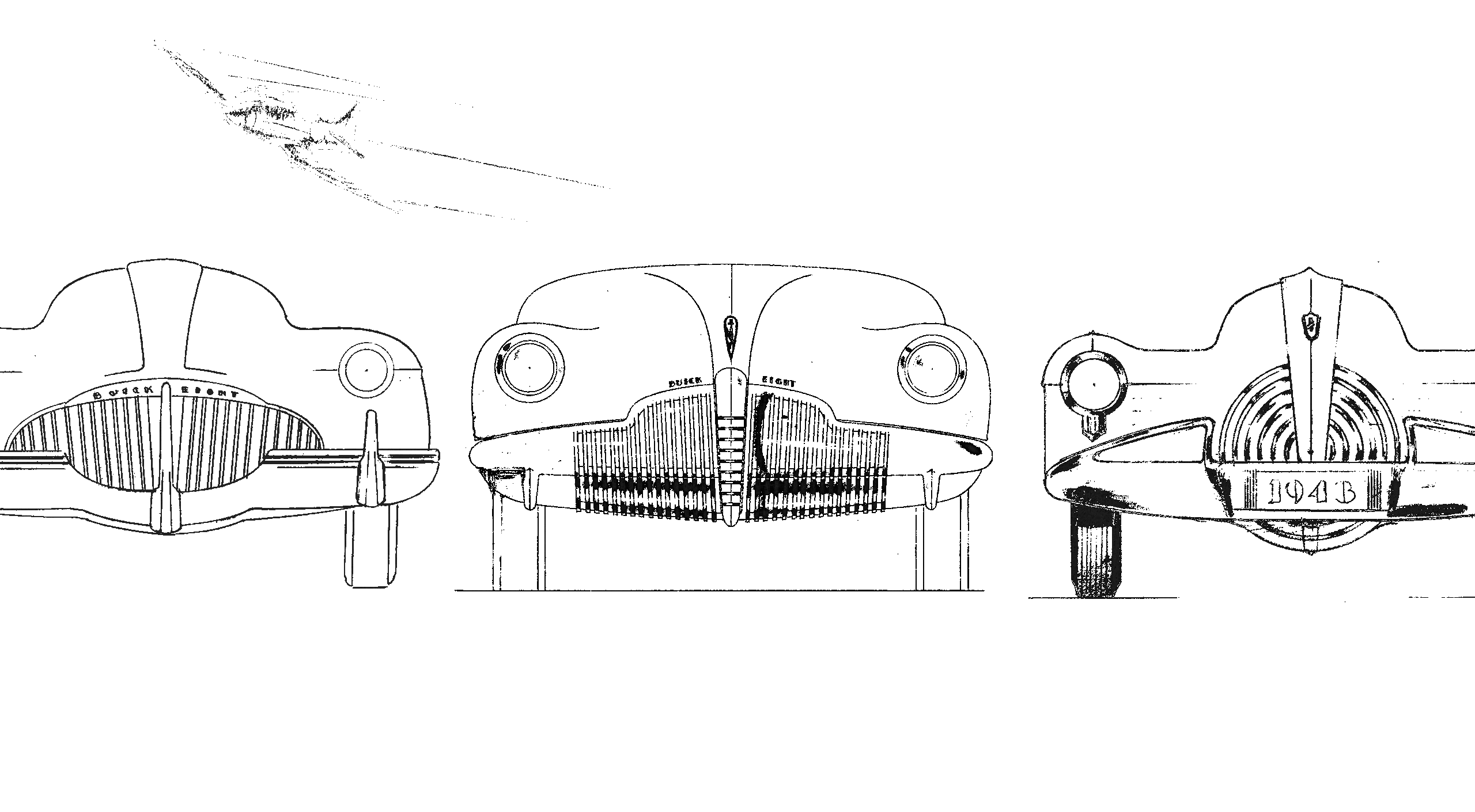

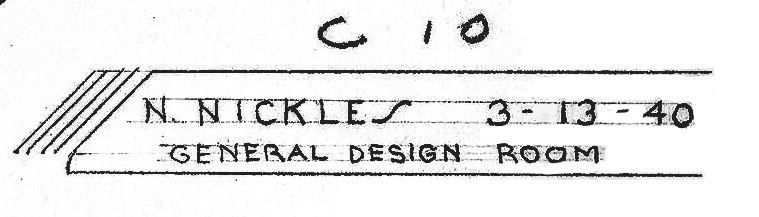

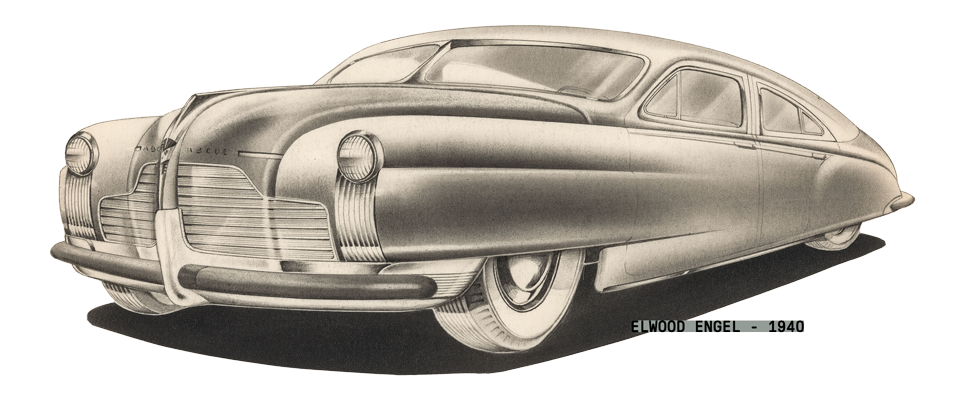

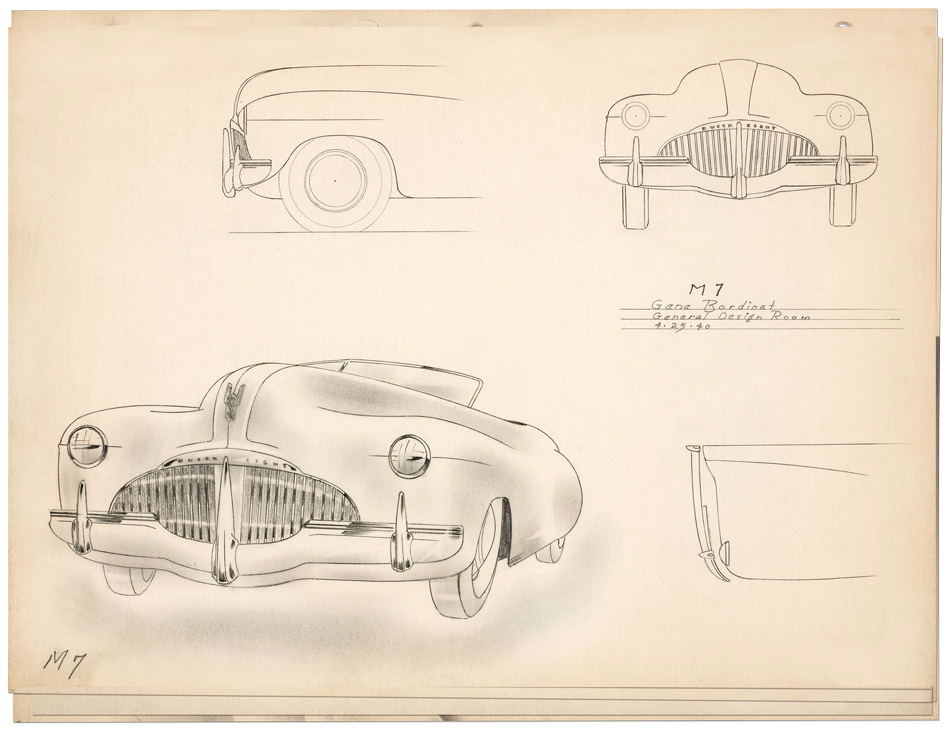

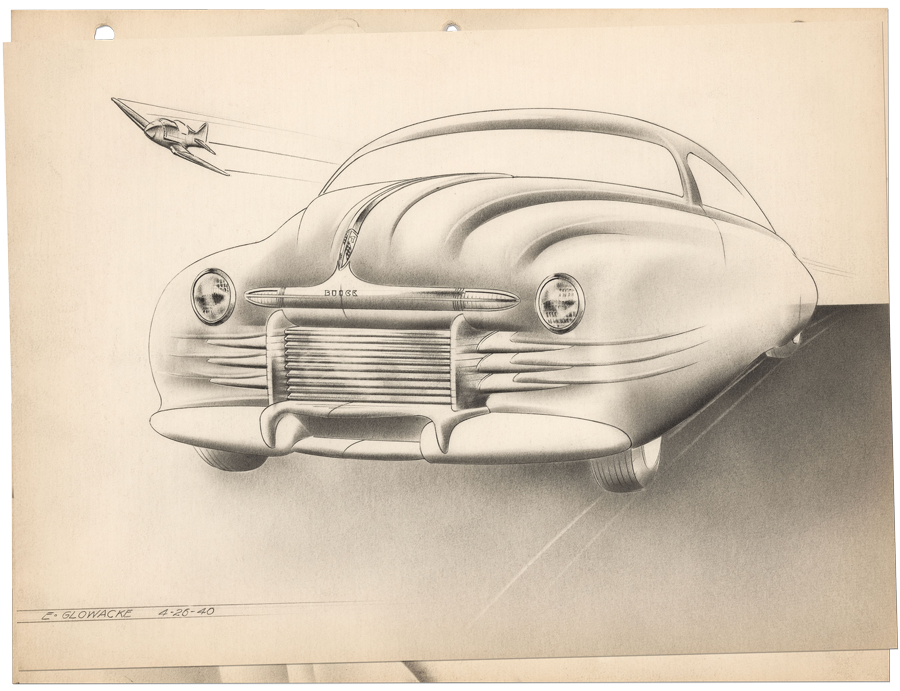

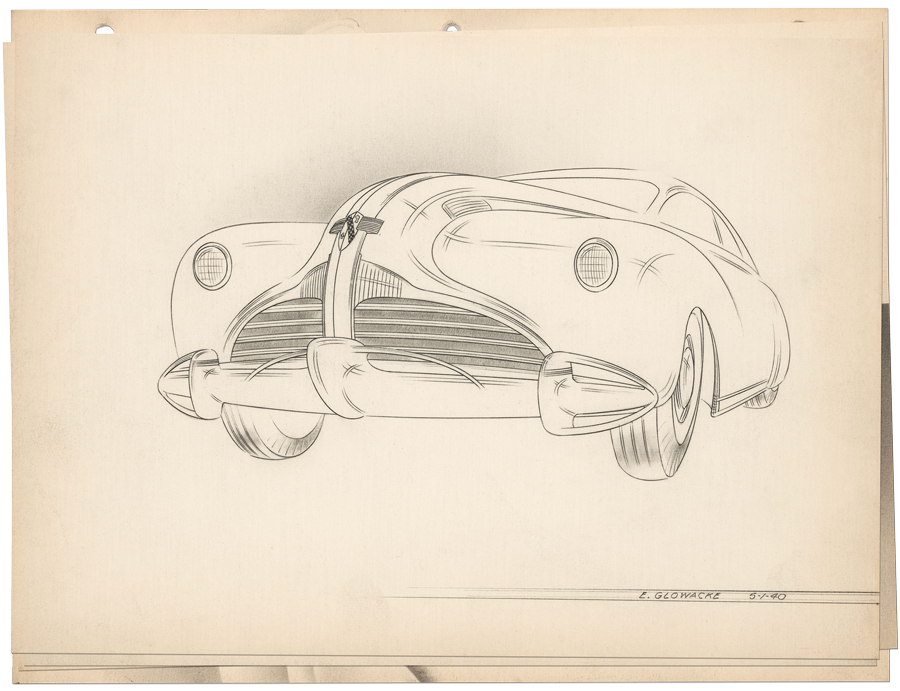

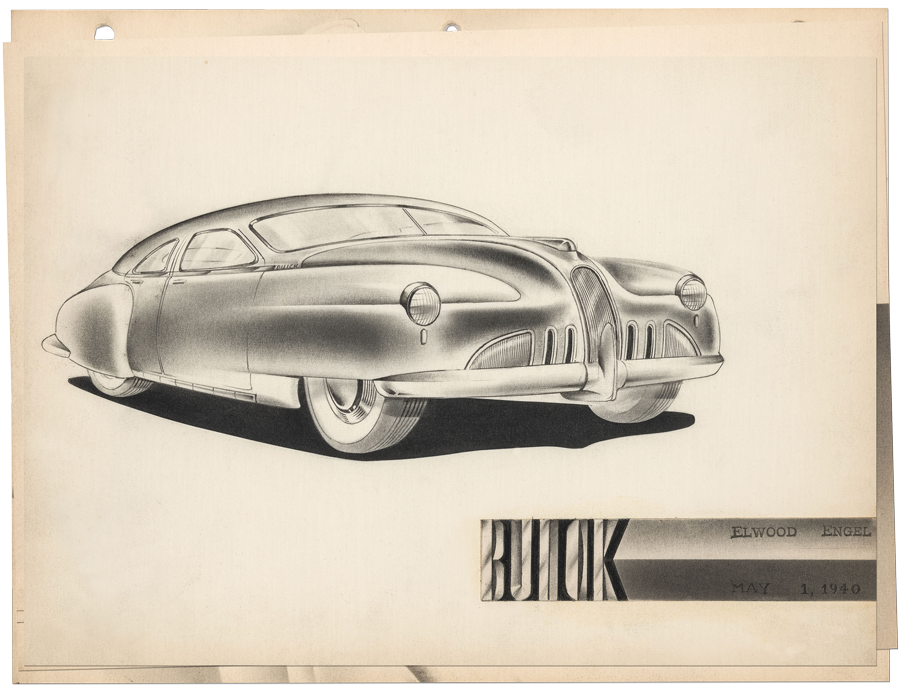

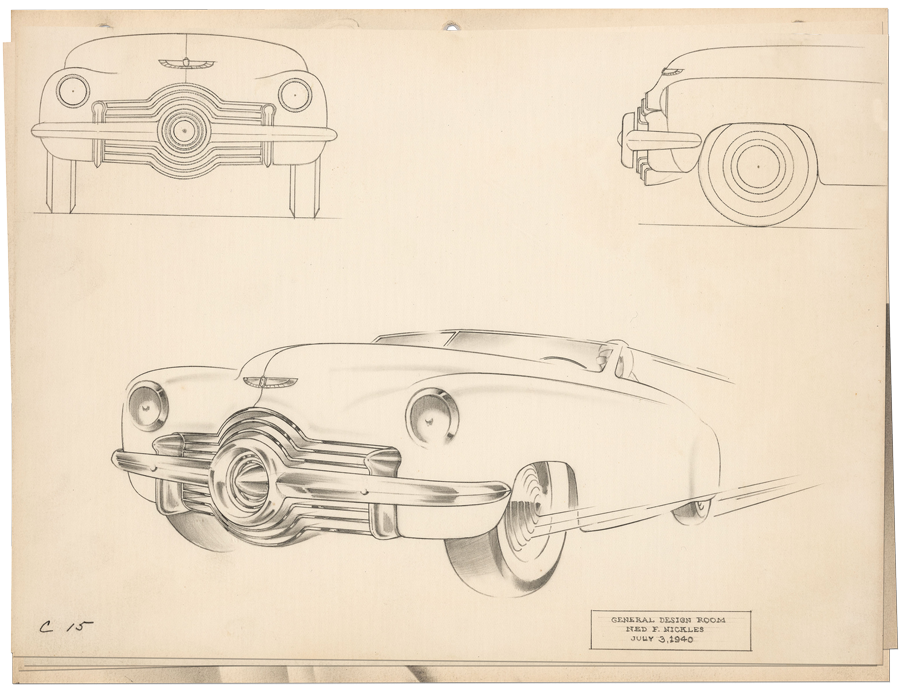

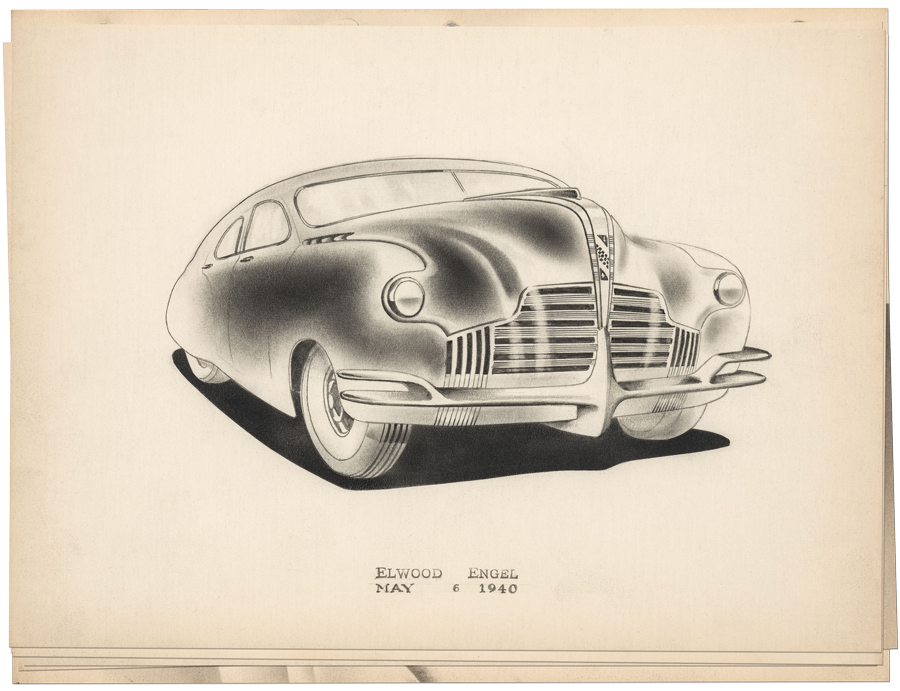

However, sometimes objects come along that fill a niche. That happened recently when YouTuber Josh Quick approached Datini with a cache of vintage drawings he’d acquired from an estate sale in upstate New York. They were not photocopies, but actual pencil drawings from an entire class in one of the Institute’s first seasons, in 1940. And the assignment was inherently interesting, asking students to create forward-thinking sketches of 1942 Buicks, a transitional time for styling as fenders, trunks, and hoods became streamlined and integrated into the body sides. It was also a model year that wouldn’t really arrive, given the conversion of much of GM’s production to armaments to support WWII.

“Most of it is relatively contemporary to that era. But some of the sketches, they have aircraft in them, showing the influence of the war and aviation,” Datini says. “And then there are a handful of sketches that were wilder, like some rear engine platforms, which was something that GM was exploring and was being explored at time with Tatra and Stout. But design is always forward-looking, right?”

Most compelling of all were the names and signatures of the students whose work is included in the cache. It represents a veritable who’s who of mid-century car designers. Clare MacKichan, who worked on the famed 1955-57 “Tri-5” Chevrolets and the original 1953 C1 Corvette; Ed Glowacke who ran the Cadillac studio during the rise of the tailfin; Ned Nickles, who later penned the perfect 1963 Buick Riviera personal luxury coupe; and Elwood Engel, who designed the slab-sided early 1960s Lincoln Continental before going on to run Chrysler design from 1961-74, defining the muscle car era.

“The main message here is that GM Design was a groundbreaking endeavor,” Datini says. “This was the forerunner of GM’s funding of transportation design programs in places like the Pratt Institute in New York, ArtCenter College of Design in California, and College for Creative Studies in Detroit. It shows that the forward-thinking vision of an institution can do this for this large company. But it also shows how GM Design was a training ground for the entire industry.” He laughs. “Because, for whatever reasons, some of those designers chose to go elsewhere.”

One response to “New Discipline”

-

. Clare MacKichan was my first executive boss when I hired in to GM Design in 1969. I never saw any examples of his design art, but he was a reasonable and decent manager, unalike many of the design executives I worked under in my over 30 years there. I do recall seeing Ned Nichols, but never interacted with him. I recall those that had worked with him speaking highly of him.

Excellent article on the storied history of the creation of the profession of automotive designers.

Recent Posts

All PostsAlloy

January 30, 2026

Peter Hughes

January 29, 2026

January 29, 2026

Leave a Reply