Digital By Design

Automotive design is industrial design. Branch out enough from the automotive core and you’ll often find the names of your favorite car designers attached seemingly incongruent objects. Pininfarina’s penned everything from soda fountains to tractors. San Francisco’s Muni light rail vehicles were, for many years, Breda trams penned by that famed design house. (Before that, the Muni trains were built by Boeing-Vertol, but that’s another story.)

Giugiaro’s Italdesign doesn’t shy away from work from paying clients, either. The Mk. I Volkswagen Golf is a masterclass in angular proportioning; the Daewoo Matiz is not. Some of the non-automotive designs that actually went into production truly changed the genre; the wild 1980s Seikos I’ve mentioned previously come to mind. Some don’t come to mind as readily.

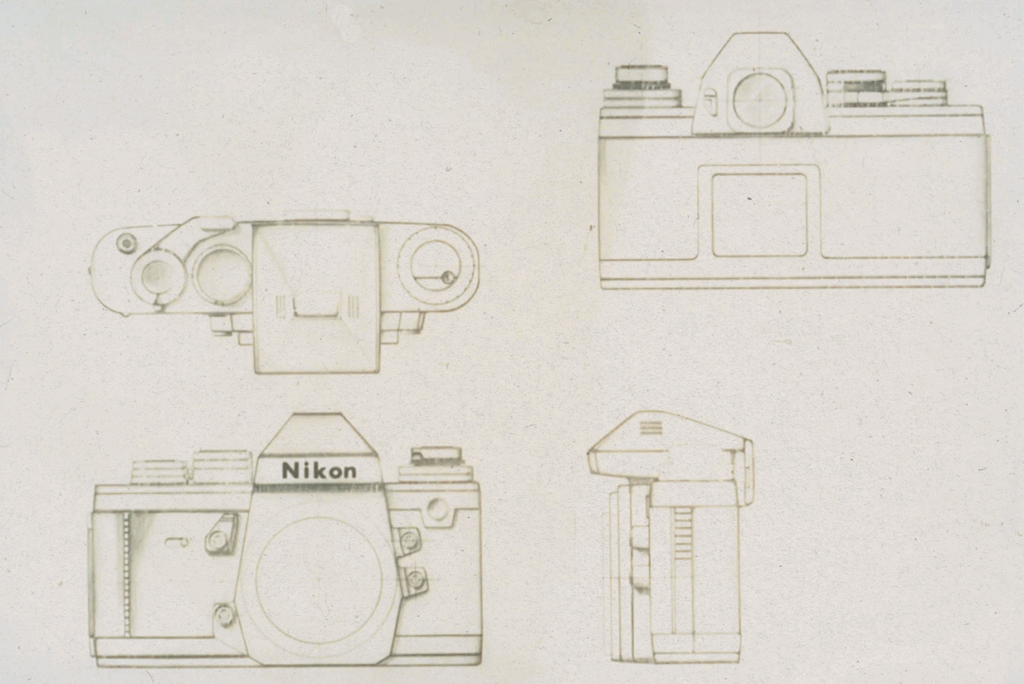

The Nikon F3 is a Giugiaro design that isn’t just aesthetically and ergonomically interesting. It also puts this Giugiaro design at the heart of a story about how digital camera technology emerged from, and then almost entirely supplanted, film photography.

By the early 1970s, Nikon was the pro camera archetype. Great optics, great systems that catered to professional needs with a massive amount of accessories, robust and reliable mechanicals. That includes mechanical shutters and manual exposure. The Nikon F2’s built-in light meter required batteries, but the camera worked just fine without them.

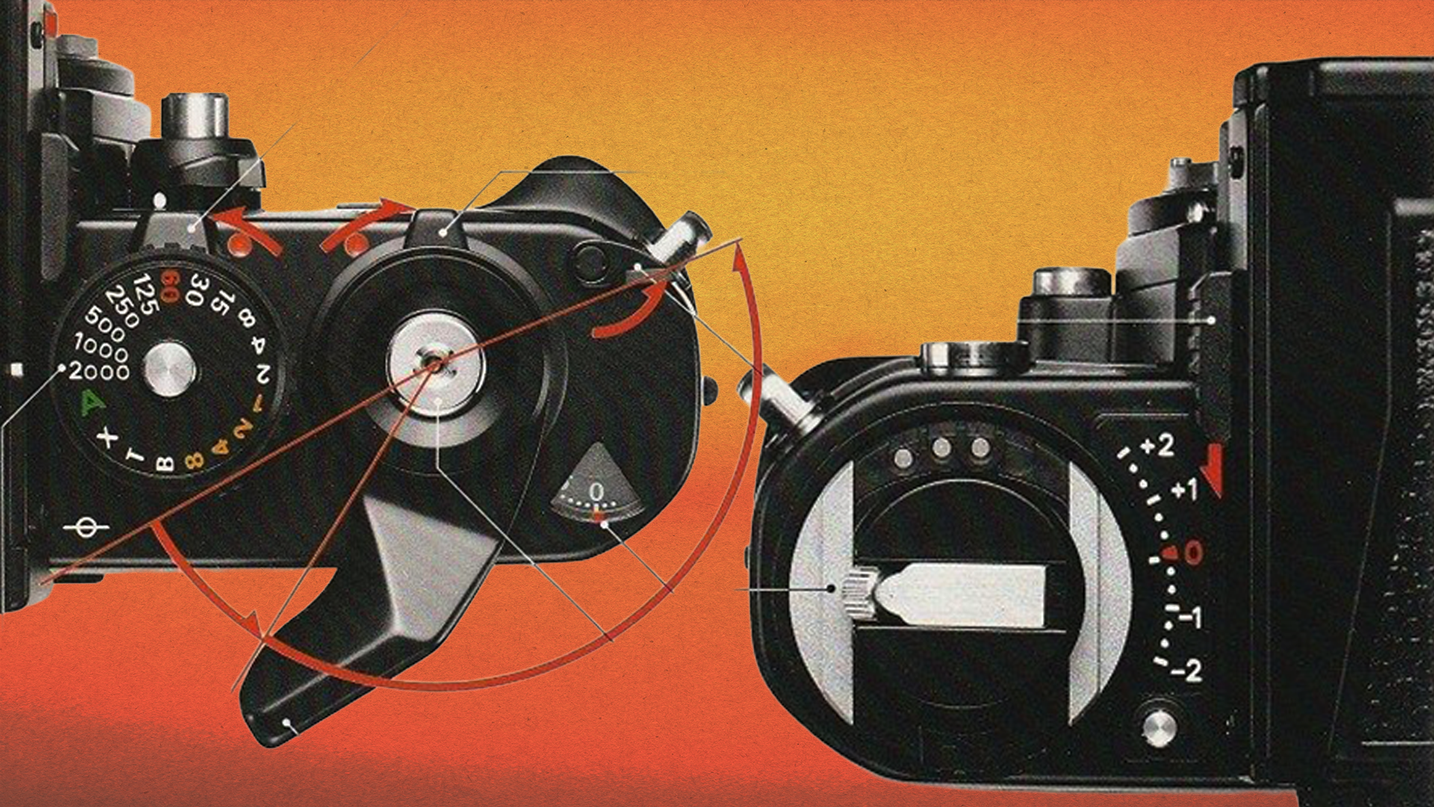

Pros loved the F2, but it was a conservatively designed camera. Its light meter wasn’t integral, but rather integrated into the commonly fitted Photomic series of interchangeable viewfinders. The clunky, lumpy viewfinders with their protruding shutter speed linkage humps were functional, but not elegant. So Nikon made two fateful decisions.

The first was to take a risk with its highly risk-averse clientele, photojournalists who prized getting the shot above all else, and complicate the camera. The Nikon F3 would rely on an electronically controlled shutter. If the batteries were dead, it would only shoot at 1/60. And it would have through-body metering, so the light meter would be housed in the body and collect light passing through tiny pinholes in the mirror. This allowed for several important advances, including semi-automatic exposure control, better flash metering, and more.

The second was arguably much less important to the highly pragmatic pro shooters and much more important to us: Nikon got Giugiaro involved in the design. The F2 did indeed look like an improved original Nikon F, designed in the 1950s. Nikon needed a careful hand to guide the series into the 1980s.

Italdesign, working within the constraints of Nikon’s engineering requirements and with the conservative target buyer in mind, delivered a clean but still utilitarian design. There’s one flourish: the vertical red line that marks where the angular and very useful integrated grip meets the body. It would become the hallmark of all of Nikon’s pro-level bodies, and the relationship with Giugiaro would continue through the F6 and D4. The integrated grip, and the accessory modular motor-drive, would strongly influence the shape of the next generation of SLRs, and eventually the full-size shape of pro-level DSLRs.

The F3 proved reliable and rugged, like its predecessor, and its technical advancements paved the way for autofocus (in the F4) and automatic film advance. The F3 itself would remain in production for two decades, well into the era of emerging digital photography. But it was a use case that Nikon could not have possibly anticipated that truly made history.

At Kodak, a young engineer named Steve Sasson had been given a device and told to find a practical use for it. The device was a CCD, a type of imaging sensor. Sasson figured out that it could capture images, determined how to digitize them so they could be stored on a magnetic tape, and display the images on a TV screen. In 1975 he had a crude but working system.

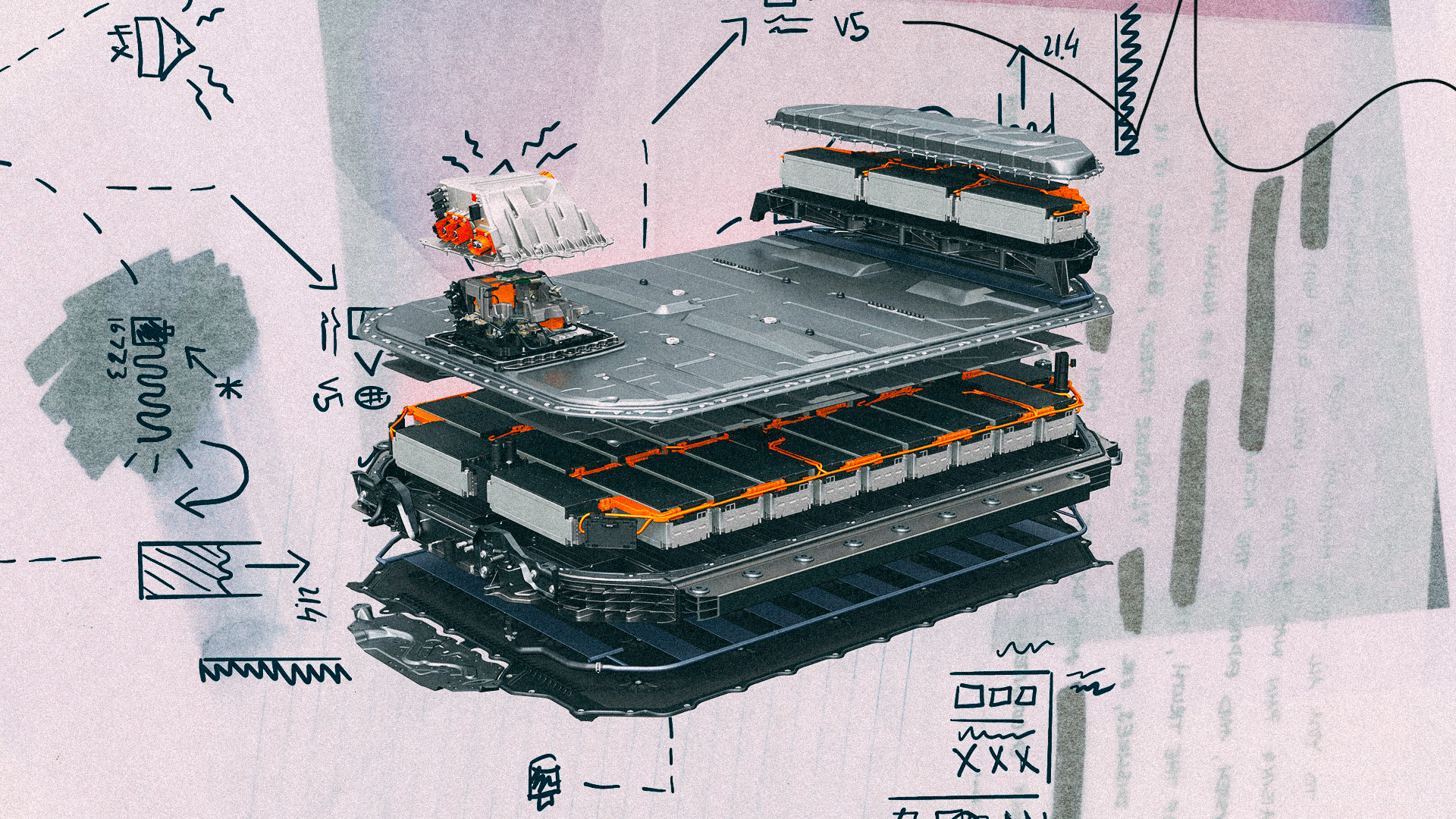

While Kodak wasn’t keen on dropping its lucrative film products, the company persisted with digital image sensor technology (and, to be fair, made quite a bit licensing the technology to other camera makers). But first, Kodak needed to build a camera that didn’t look like something kitbashed from an abandoned Radio Shack, something the company could use to sell the technology to photojournalists. It developed an enormous, clunky processor and storage device known as the Digital Storage Unit, hooked up to the 1.3 megapixel CCD sensor by a physical cable. With 200 MB of storage capacity, it could hold 156 images. You could carry it with a bulky hip pouch provided by Kodak while it was tethered to the capture device, which was separate from the processor and storage unit.

By 1991, the Digital Camera System (retconned later as the DCS 100 after follow-up systems emerged) was ready to sell to consumers for $20,000—that’s not adjusted for inflation. So by consumers, I mean that maybe the largest newsrooms in the country could afford one.

Somewhat strangely to the modern observer, Kodak decided not to develop anything on the camera itself—the body, the optics. The company decided that the Nikon F3 was the perfect “front” for their digital back—a term for a digital sensor that can take the place of the film compartment on some cameras even to this day, allowing them to capture analog or digital images by swapping out the film holder. The sensor was embedded in a plate that replaced the rear film door, putting it in the same place as a frame of 35mm film. The capture area was a bit smaller than a full 35mm frame, so some guidelines were added to the viewfinder.

This was a savvy choice for a couple of reasons. For one, the camera itself handled just like the Nikon F3 that many photojournalists had by this point fully embraced. As a bridge between digital and analog, it was a brilliant move. Giugiaro’s red-accented, angular, visionary camera body would form the basis of the very first digital SLR camera available to the public.

The subsequent early cameras in the Kodak DCS line can really be thought of as kind of modification packages of various film bodies. It would kind of be like if Panasonic signed an agreement with Nissan to supply Versas to convert to be full BEVs, destined to be a short-term arrangement because Nissan would be developing the Leaf on its own. These alternate-universe EVs would be badged as Nissans but sold as Panasonics. It kind of makes sense, but it would end up being a little short-sighted for Kodak.

That’s because while simply making the sensors was lucrative, camera manufacturers were hard at work on their own sensors. And once they had those, they didn’t need Kodak anymore. Kodak probably could have purchased a struggling film camera manufacturer—there were several in Japan that had fallen behind Nikon and Canon and were spiraling the drain—and gotten into the business of making entire cameras. But Kodak did not. Nikon, Canon, and many others still make digital cameras. Eastman Kodak went bankrupt.

It should be noted that Kodak emerged from bankruptcy and still producing film to a strong following of hobbyists and professionals that still love using it. But it’s not anything like it once was, or could have been.

But back to the Kodak DCS. Nikon (and later Canon, and finally Sigma) would supply film camera bodies that Kodak would utilize for DCS models for quite a while. While the processor and storage units were integrated into the body starting with the DCS 200, it was still a large, clunky affair grafted onto the bottom of a film body like an oversized motor drive. Later DCS cameras more closely resembled the first wave of the full-sized pro DSLRs like the Canon EOS-1D in 2001.

Kodaks’ DCS business would peter out in the early 2000s, but it had given the companies whose bodies it used the confidence and established track record to develop their own DSLRs. And we have a Giugiaro-designed Nikon to thank, however indirectly, for it.

One response to “Digital By Design”

-

Great article.

Those very early digital cameras had all sorts of quirks. I was on a stop-motion project in the mid-nineties that procured the loan of 3 of Minolta’s first run of digital cameras (from a batch of 60, and not for sale commercialy). They lacked a video screen on the back (which would’ve been useful), utilized the early version of the little photo memory cards we still use, but could only hold 64 or 128 pictures per card (depending on card size—and this was at the old TV res of a mere 480x320p). The camera was exactly as described here: a 35mm SLR body with a digital underbody. Allowed the use of all their very nice lenses, which was great. But they liked to overheat and fry the memory cards, destroying all the photos you’d saved. We had to set up fans to cool the digital underbody, but still lost a few hours of work from time to time. As fun as stop-motion can be, it’s a lot less fun to reanimate a scene you’d just finished—esp’ly at 2 in the morning!

Minolta might’ve been the best candidate for Kodak to acquire. But very grateful that Kodak still manufactures real film—both for still cameras and motion pictures. Let’s hope that continues!

Recent Posts

All PostsAlloy

January 30, 2026

Peter Hughes

January 29, 2026

January 29, 2026

Leave a Reply