Rally Hard

November 4, 2025

Alex KiersteinHonda just built a Civic Type R rally car. Then two chuckleheads drove the untested show car more than 1,000 miles to SEMA.

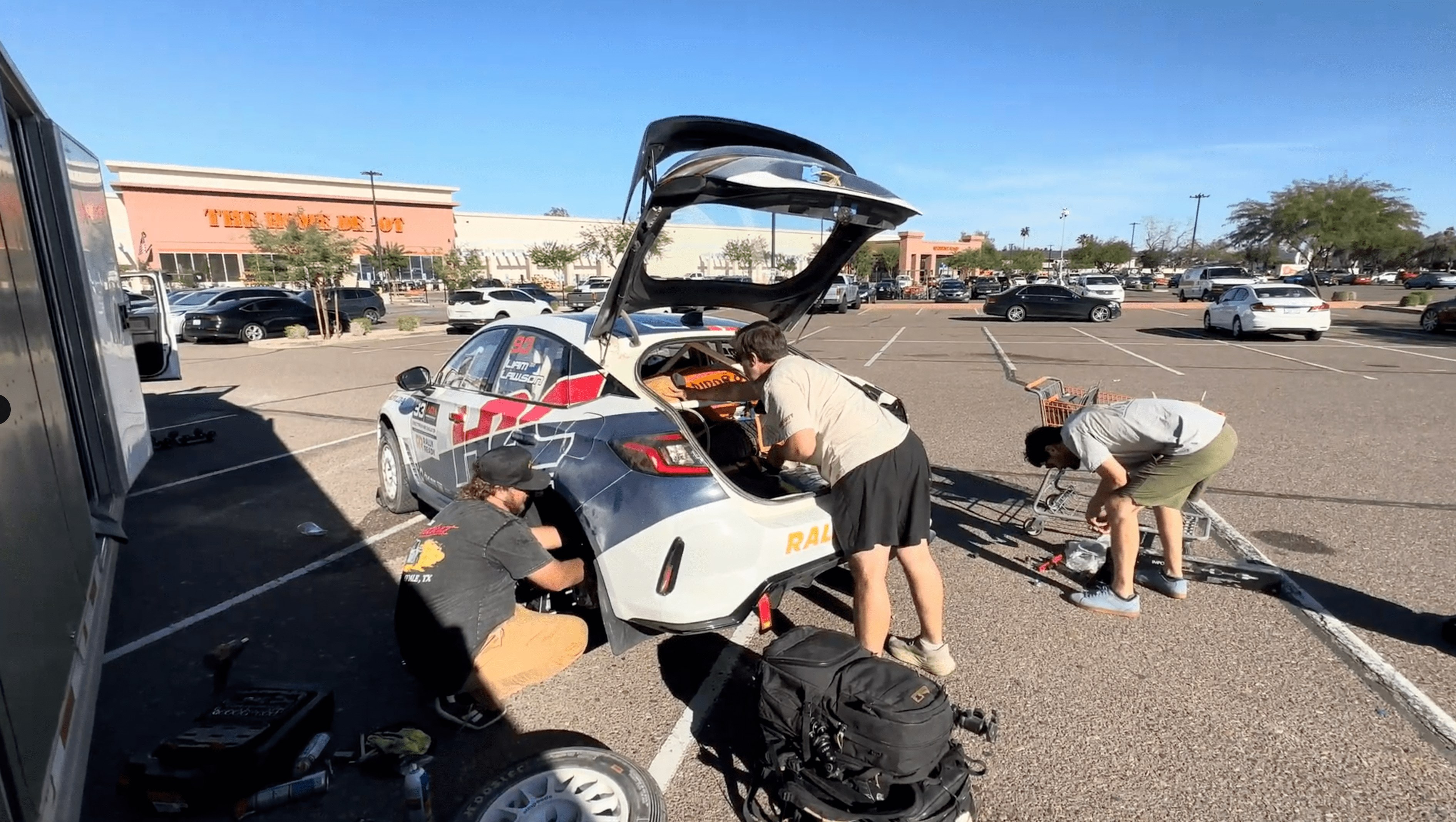

“I thought it was a funny thing to say out loud, that we should road-trip it to SEMA,” Dave Carapetyan says to the camera, a hint of concern underneath the self-effacing tone. “And then somebody overheard me and they thought that was a good idea.”

Dave says this at his Rally Ready driving school. He’s the founder and CEO, known to some as “Texas Dave,” and known to Pikes Peak racers as a long-time competitor. (Incidentally, his rookie run up the hill was in an Acura Integra, his first rally car was an Integra Type R, and he is to this day a self-described “ultimate Honda nerd.”) Honda’s racing division tasked him with turning a Honda Civic Type R into an honest rally car, ready for competition. And also that it be made ready for the SEMA booth. In two days.

His trip-mate, Detroit startup polymath, rally driver, and good-natured masochist Andy Didorosi, cheerfully notes that the car’s covered only roughly 50 miles since the build wrapped. Much of that was a slidy photo shoot with Red Bulls F1 driver Liam Lawson. At the ranch. Zero road-going (i.e., transit) testing.

Andy tells me later, “Everybody is so serious in rally all the time. We’re trying to bring a little heart and soul into it again. Everybody can’t be fist pumping in the air as golden light bathes over them as champion number one. It’s a silly thing that we’re doing.”

Back at the Rally Ready ranch, Dave contemplates the silly thing he is doing.

“I’m so sorry for who I am as a person,” Dave says, mostly joking. Andy grins widely. It’s going to be brutal. They are very excited.

Rally, and Honda, both exist in a performance nexus of sorts. Everyone likes to slide around in a fun car, but few are willing to stand in the woods for hours to see cars scream around a single corner. Fewer still are willing to put it on the line and race themselves. It makes rally a niche sport, underappreciated, despite a fantastic fan culture and an unparalleled adrenaline hit for competitors.

Honda is one of the few manufacturers of front-drive performance cars left standing. But unlike some of those other manufacturers, Honda has only a limited history in rally, mainly in European series.

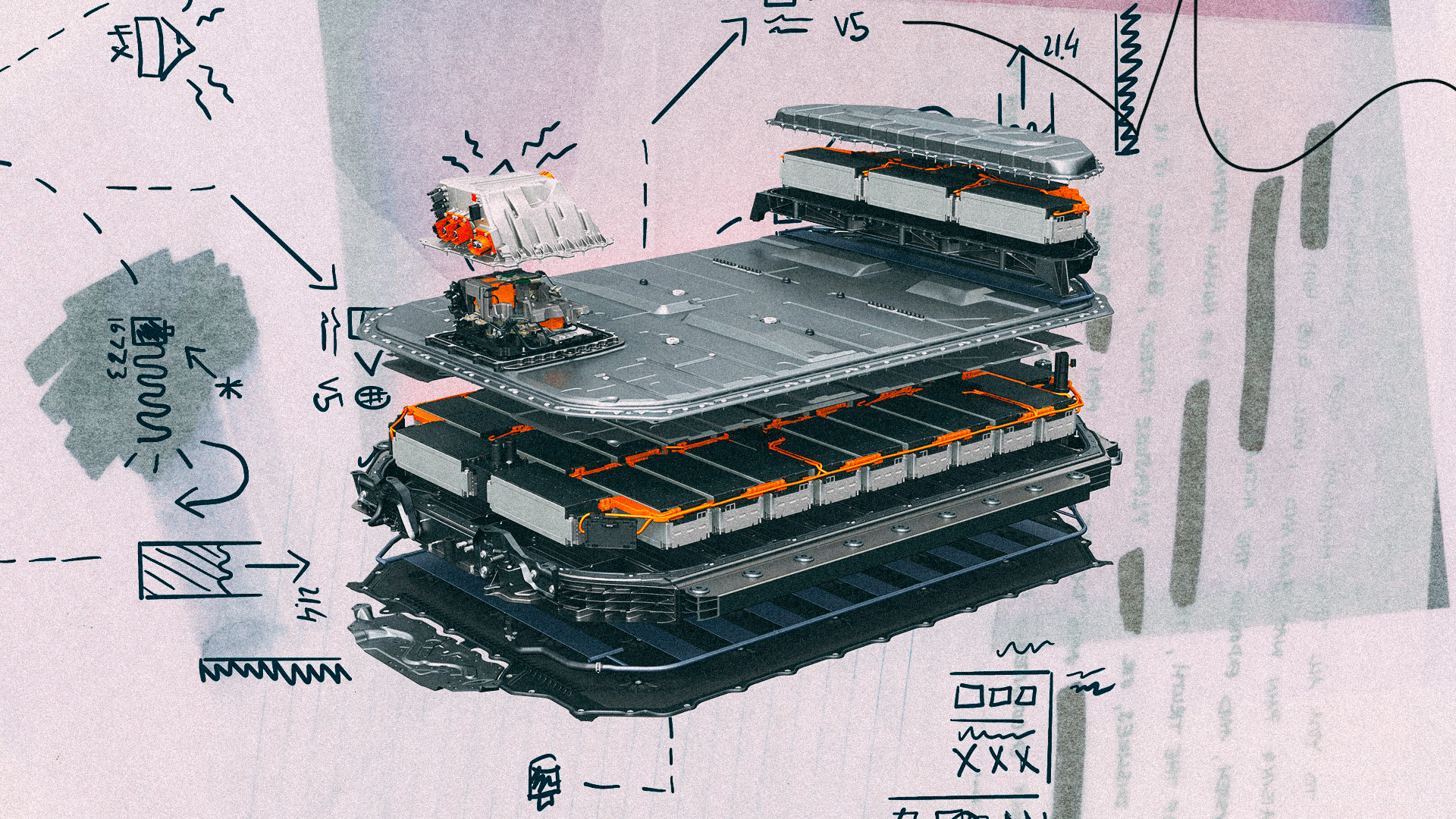

That’s what makes Honda’s SEMA show car so unique. It’s an honest rally car, built by a shop and rally driving school in Texas well-versed in the art—Rally Ready—and built from a new Honda Civic Type R. The one with a boosted 2.0-liter making 315 hp in stock form, sending it all through the front wheels. It works due to a mind-bending arrangement of clever suspension setup, a limited-slip differential, and advanced traction management.

The Honda Civic Type R Rally XP is a JDM limited edition-worthy name, something you could unlock in a Polyphony Digital game. But it’s also part of Honda’s performance realignment, and not just for its rally focus. For decades, Honda’s racing divisions were bifurcated. Honda Performance Development was an arm of Honda’s American division, created in the 1990s to go racing in the IndyCar series. Meanwhile, in Japan, Honda Racing Corporation was created in the 1980s and branched out from motorcycle racing to, eventually, the company’s Dakar rally program and finally, in 2022, the F1 program.

Now they’ve combined, under the HRC banner. Honda has decided that the two arms can support each other, both in F1 powertrain development and in sports car racing. The Acura ARX-06 LMDh car switched to wearing HRC livery in 2024. And that’s why the Type R Rally XP is an HRC product.

But what is it, exactly? A show car that’ll be at Honda’s SEMA display in Las Vegas. But it’s also an honest rally car, built to American Rally Association Limited 2WD spec with the following parts:

- Rally Ready PFC monobloc brakes (309mm front rotors, 255mm rear rotors)

- Dual master cylinders with balance bar and bias adjust

- Rally Ready/Ohlins TTX/TPX gravel dampers

- Hoosier gravel rally tires

- Speedline 2118 gravel rally wheels

- OMP HTE seats

- OMP One harness

- HRC tuned ECU/engine management applied by Hondata FlashPro

- Acuity billet shifter

- MOTEC C127 dash display and controls

- HRC TCR cooling ventilation

- FIA compliant roll cage

- Carbon fiber handbrake

- OMP co-driver footplate

- OMP 4 liter fire suppression system

- MOTEC C127 dash display and controls

- Zero Noise Fury Intercom

- Rally Ready/HRC stainless exhaust with rear catalytic converter

- HRC intercooler and oil cooler kit

- HRC/PWR radiator

For HRC, this is a bridge from touring car racing, which Honda has a strong heritage in, to rally. And it has precedent. Honda America Racing Team, a racing outfit run by Honda employees, fielded a Limited 2WD Integra at a host of events over the last few years. The Integra and the Civic Type R are similar, so the experience should help this factory HRC car get dialed in quickly should Honda decide to contest a whole season.

Bringing in Rally Ready is a sensible move. Automakers frequently partner with rally specialist outfits to do the development and construction of their cars. Think Prodrive for Subaru’s WRC cars during the heyday, and Vermont SportsCar for Subaru Motorsports USA in contemporary ARA. Rally Ready could be this for HRC, especially if the response at SEMA is strong.

But the car has to get there first, in one piece.

Andy has a theory about what prompted Honda to take rally more seriously.

“I think it all goes back to that time Max Verstappen was talking shit about front-wheel drive,” Andy explains to me on the phone. He thinks it lit a fire under Honda’s ass, prompting the company to explore ways to indirectly rebut Verstappen’s pointed critique. There’s no evidence that this influenced Honda whatsoever, but it’d be delightful if it was true.

Different corporate teams have competing agendas, and timelines. Honda wanted the car on the SEMA show stand. While the car has been planned for a year, and the build wasn’t rushed per se, the sort of high-pressure, high-stakes scenario reserved for “unscripted” reality shows emerged.

The build just finished. The car isn’t tested. If we don’t make it to SEMA in two days with a spotless car, we’ll lose the shop.

And it went just how you’d imagine.

Andy and Dave are both experienced rally competitors. Andy earned an ARA class championship in a Subaru Impreza RS. Dave is, well, Texas Dave. They may not be taking things too seriously, they may have impulsively agreed to do something mildly irresponsible, but they are not neophytes. They know rally cars are hot, loud, and designed for stints. Transit stages—the regular-road driving from one leg to another—put all of the emphasis on the things the car is no longer good at

“We basically took the most arduous part of rally driving between the stages in a rally car and made it three whole days,” Andy says. He and Dave call the trip “Oops, All Transit.”

It’s not like the actual process of rally competition is a vacation, either. A long day of recce in a rental car, to build the navigator’s notes, and a long night of making sure you got it down. (So you don’t die. No pressure!) The added hit to energy of socializing during parc expose. Then, as Andy tells it, six to ten hours of straight competition, with all of the anxiety and endorphins that provides, broken up by the monotonous sensory overload of transit. Even the stages hit different, since it’s not door-to-door racing. It’s just you and the co-driver and the trees whizzing by.

At one point, the guys spend the night at some bizarre ranch in Texas because a buddy let them crash there. The decor is partly cowboy (swinging half-doors) and partly elderly relatives (lace doilies), a mix so amusing that the 3:00 AM arrival and early wake-up don’t break the mood. Until the next morning, when Andy asks about the water temps randomly, from the back seat, for no particular reason.

“Oh shit,” is Dave’s response.

The fans aren’t running, which is bad. It’s Texas. Even in early November, the ambient temperature is in the high 80s. The water temp gauge reads 230. The coolant reservoir has responded by cracking, so now the car’s hot and leaking coolant. The car itself is also very hot inside. Remember, fixed side windows, no A/C, Texas.

“And that’s when,” Andy tells me, “[I think,] oh my God, are we actually in real physical danger here? Broken down overheating. We brought very little water ourselves, which is a total, it’s really a story of hubris, sort of like a buddy cop film that’s just ripe with hubris all throughout.”

They try to turn the car around.

It won’t go into reverse.

I’d like to tell you they fixed both of these issues, but they didn’t. No time. 1,200 miles to go still, on a strict timeline. They borrowed the car from Honda promising it’d be at the show in time to make it onto the floor, and here they are, 200 miles from the starting point, adding coolant every 90 minutes and with no reverse gear.

The reverse thing isn’t Honda’s fault.

“We installed it minutes before we left because Honda wanted this specific shifter in there. And there’s three adjustments on that thing, which you have to use the factory service manual to do. These are things that normally people take weeks to figure out. And here we are trying to jam it all into minutes and then paying the price.”

On the phone, Andy describes his dehydration, fatigue and the stress of what they’d agreed to (unnecessarily; a vehicle transporter was a completely valid option). But it prompts us to reflect a bit about what makes two guys who know better gleefully hop into a completely unsuitable car for a couple days of torture.

I tell Andy about the time I drove a Porsche 996 GT3 RS. It was a Porsche Museum car, and we were at the Isle of Man. Unfamiliar roads, poor weather, and an uncompromising car. It took complete focus, partly because everything was so direct. I swear there wasn’t a shred of rubber in that car save the tires and hoses. Certainly not in a single bushing. After 40 minutes, I wanted to lie down and nap. I couldn’t stop thinking about it for days. Daydreaming about building a clone. I still do.

I ask Andy if the physical demands of driving a car totally unsuited to the task for thousands of miles under the pressure to succeed holds that kind of appeal.

“Yeah. I mean, it’s so complex … [we are] both multiple business owners. We’re extremely busy. The more successful we get, the less time we have to actually do rally and be in rally cars,” Andy says.

“The more successful you get, the further away [you get] from the thing you originally signed up for … I can’t leave the car. You can’t leave the car.”

He compares it to flying the Spirit of St. Louis. Primitive, uncomfortable, highly specialized. “You can’t have a meeting in a propeller plane over the Atlantic.”

That, I can understand.

Recent Posts

All PostsAlloy

January 30, 2026

Peter Hughes

January 29, 2026

January 29, 2026

Leave a Reply