Art & Science

I’m wearing a Casio F-91W right now. It’s about the most minimal multifunction digital watch you can imagine, and there’s nothing objectively noteworthy about it. It’s inexpensive (and looks it), it has four functions (one of which is setting the time), and is churned out in some vast Asian factory autonomously, without the assistance of human hands. It’s been associated with bomb-makers (and accused bomb-makers) who like it for the same reasons I do, and that doesn’t color my opinion of it any.

There’s no craft in its creation, but there’s also something magnificent about it. Something pared down to its simplest possible form. There’s nothing extraneous here, and that also makes it thin and light. It’s the only watch I own that I can tolerate wearing on its resin strap, which is good because it’s minimally secured with an untapered, pressed-in pin. It has gone years without a battery, keeps time more accurately than my G-Shock square, and has been thoroughly abused. It is covered with scratches. A new one is about $20; the numerous clones are more like $6. I will keep mine running until it absolutely refuses to turn on.

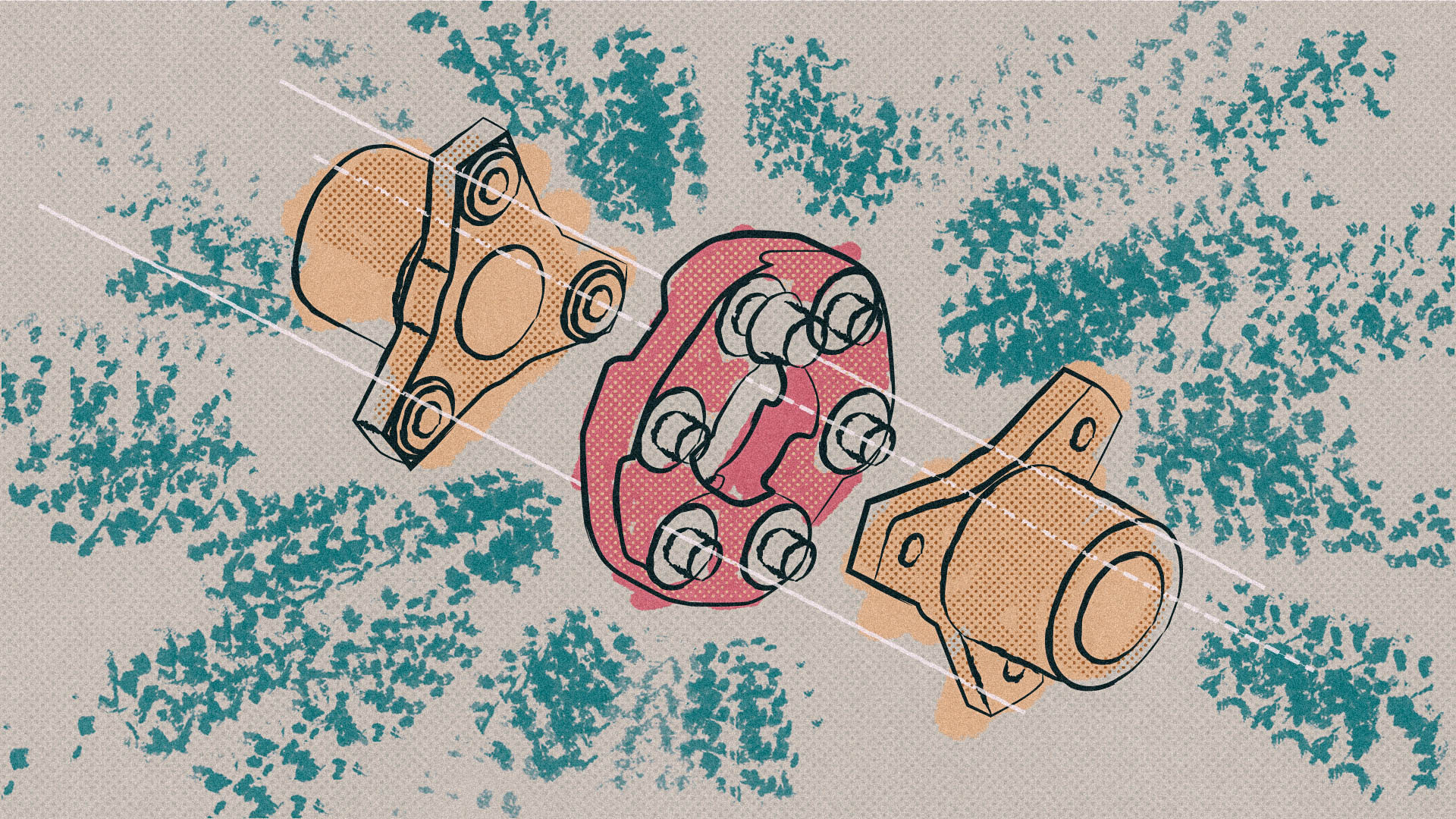

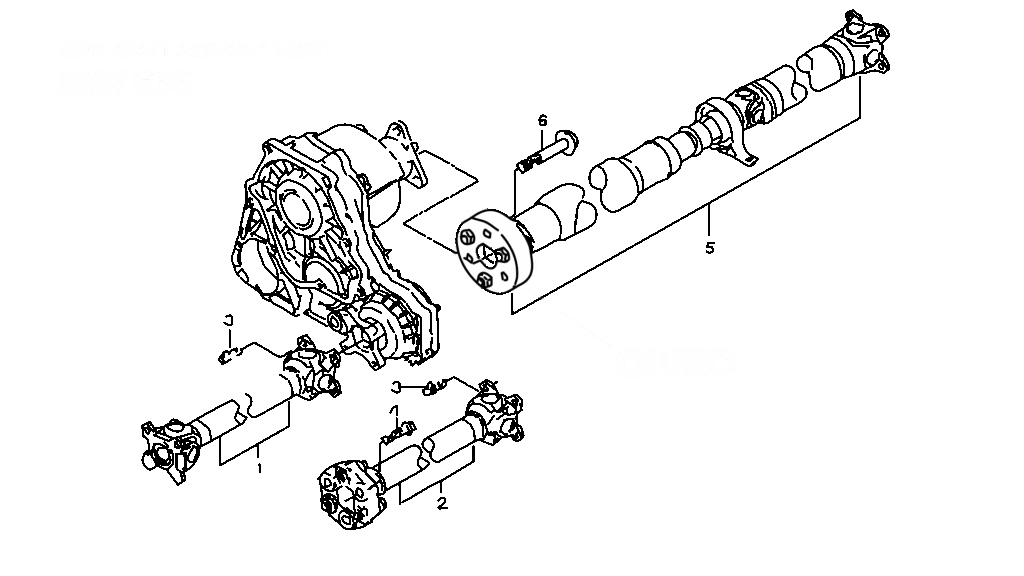

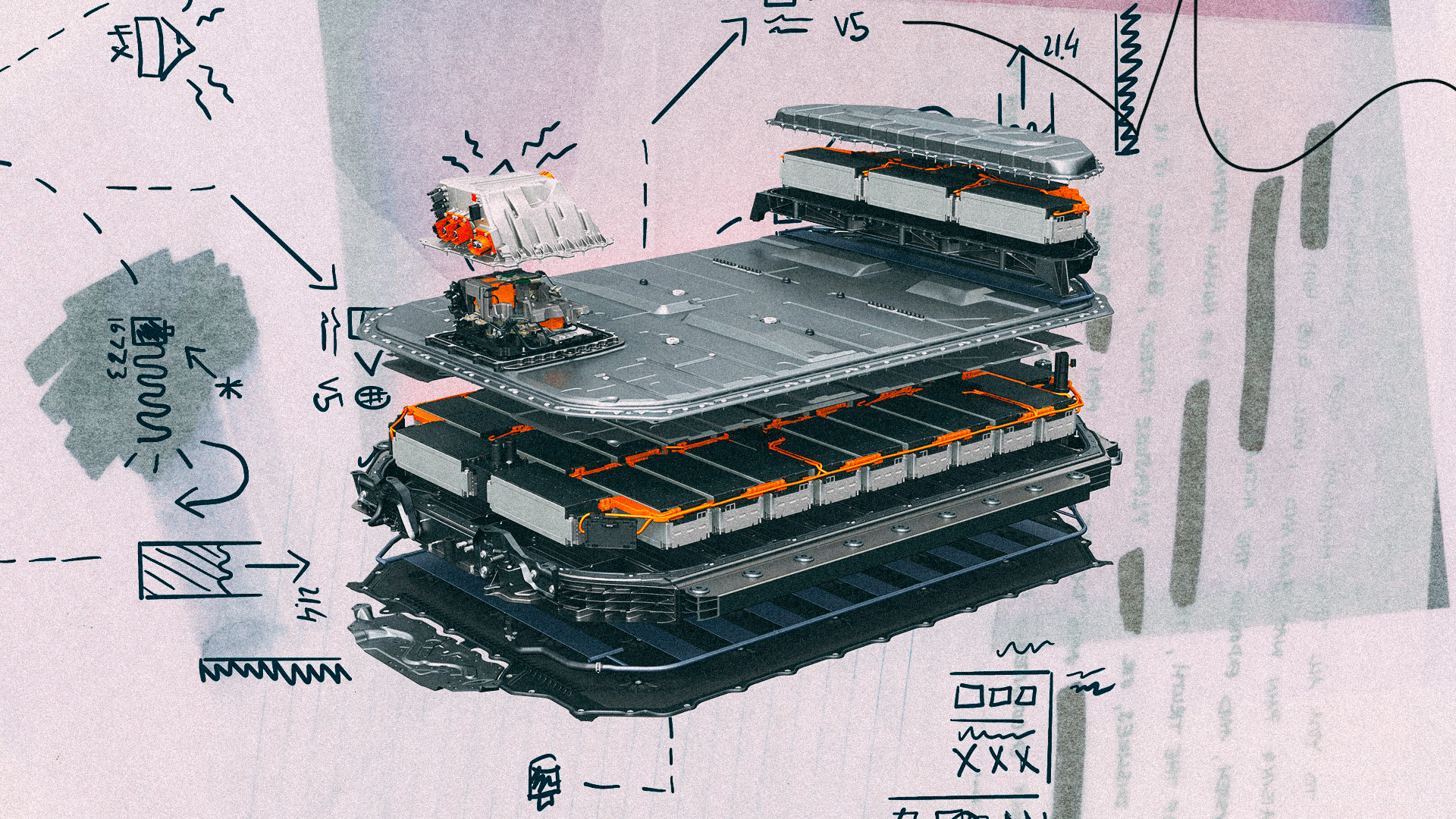

That’s why, beyond its mispronounced, misspelled name, I can appreciate the giubo. An elegant solution to a real engineering issue, a simple shape, two basic materials, and a serious benefit to the driving enthusiast. The giubo was the invention of Antonio Boschi, an engineer working at Pirelli. A rubber coupler designed to replace the u-joint between the transmission and the driveshaft, its flexibility absorbs driveline harshness and motion from the suspension. In addition to reducing NVH, it extends the life of driveshaft components.

Giunto + Boschi = Giubo

“Giunto” means joint in Italian, and so giubo (jyoo-boh) is a portmanteau for, essentially, “Boschi’s joint.” The giubo was a great success for Boschi, an occasional headache for BMW and Mercedes-Benz owners, and this is about where the average enthusiast’s knowledge of the man ends.

Boschi went to war as an airship pilot.

But Antonio Boschi’s life was considerably more interesting than the story of his driveshaft donut. Boschi was born in 1896 in Novara, a town west of Milan. When he was 19, the Italians entered World War I on the side of the allies, and Boschi went to war as an airship pilot. There was a stint in Hungary working in railroads.

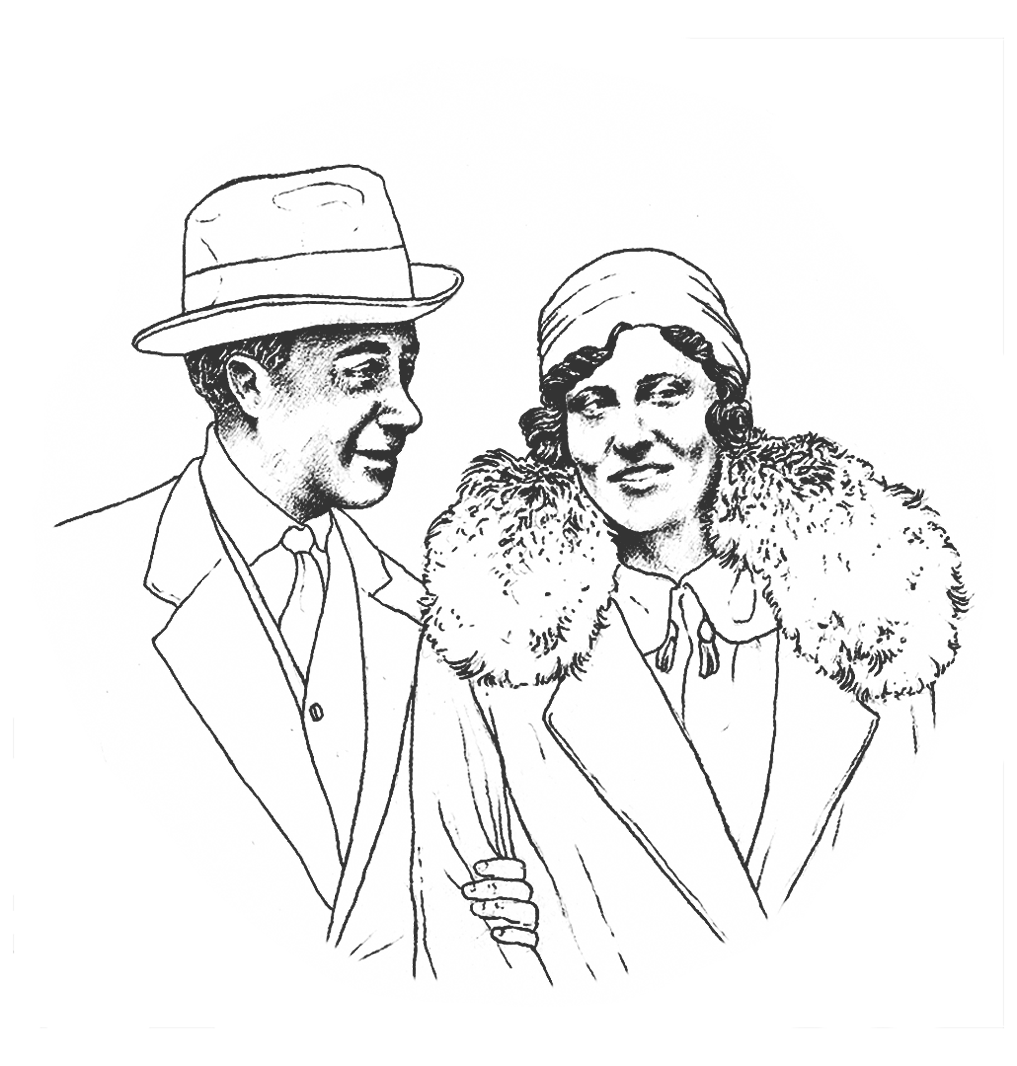

And in 1927, Boschi married sculptor Marieda Di Stefano. The rest of their life was filled with love for each other and an equally intense love for art. (Storie Milanese, an intensely interesting virtual tour of Milan through the stories of 17 of its famous residents, has a beautiful piece with more details about their life that I drew from. You should read if you’re interested in Italy’s 20th century art scene.) Their eclectic apartment in Milan was, at the time of Boschi’s death in 1988, stuffed with more than 2,000 works. Sculpture, paintings, interesting furniture. The apartment was donated to the city of Milan, which made it a museum. It is free to visit, one of four case museo di Milano—Milan’s house-museums.

The couple collected works from Giorgio de Chirico—a painter whose work had a lasting influence on, among many others, David Bowie and Fumito Ueda (known for the cult classic games Ico and Shadow of the Colossus)—and de Chirico’s younger brother, the multipotentialite Alberto Savinio, an opera composer, essayist, and more.

Around 300 works remain at the Casa Museo Boschi di Stefano, which is operated by the Fondazione Boschi Di Stefano, according to Boschi’s wishes at the time of his death. And it’s a fascinating addition to the lore of the giubo, that a man whose deceptively simple solution to a complicated engineering problem also left behind a legacy of cultural patronage shared with the city he loved.

One response to “Art & Science”

-

I would have sworn on a stack of bibles these were called “guibos”. I would have put money on the line, even. I have without question said the word “gwee-boh” more than once in polite company.

If only I’d known then what I learned now…

Recent Posts

All PostsAlloy

January 30, 2026

Peter Hughes

January 29, 2026

January 29, 2026

Leave a Reply